As we know, Rift-tech had an enormous impact on military technology in the later 1940s, making the battlefields of Konflikt ’47 vastly different (and more lethal!) environments than their Bolt Action predecessors. While the genetic monstrosities, artificial intelligence, and high-tech firepower are all rightly icons of the setting, perhaps none are quite so famous and beloved as the walkers – after all, who doesn’t love a huge, stompy tank-on-legs?! Let’s take a look at their history, rules, and how to go about using them on the tabletop.

The very idea of a ‘walking tank’ had captivated scientists and military theorists of all nations during the interwar years. Many envisaged a vehicle capable of traversing terrain that a tracked or wheeled vehicle could not, particularly in urban or forested areas, that would mount heavy weaponry and boast thick armour. This was, at least until the opening of the Rifts, a pipedream – the very earliest experiments revealed insurmountable issues with servomotor actuation, and most importantly with gyroscopic stability – put simply, it was impossible to mimic an organic system with the technology available at the time. Rift-tech changed this, almost overnight.

Almost simultaneously, American and German scientists made a series of breakthroughs in the field of gyroscopics, most notably the discovery of what would become known as the Hedley-Kaye Principle. A fiendishly complex concept, it revolutionised what was possible when creating miniaturised artificial stabilisers, and was immediately utilised to great effect in upgrading the gyro-stabilised guns found in many US tanks, as well as in German experimental missile guidance systems. The RAF too found the technology useful for bombsights, and it was here that it caught the attention of one Group Captain Ware of the War Office’s Experimental Division. Ware, a railway engineer by trade, had been heavily involved in the pre-war studies on the possibility of walker development, and realised that the Hedley-Kaye Principle made the concept worth revisiting. Initial experiments were conducted at the Hunslet Engine Company, before being shipped to the USA in greatest secrecy, where development was rapidly accelerated with the industrial might of America. In Germany, meanwhile, scientists came to a similar realisation, and high command seized upon the idea with great enthusiasm, ordering a light reconnaissance walker straight off the drawing board – this would go on to become the Panzermech I ausf. A, known as the Spinne (spider) for its arachnoid appearance.

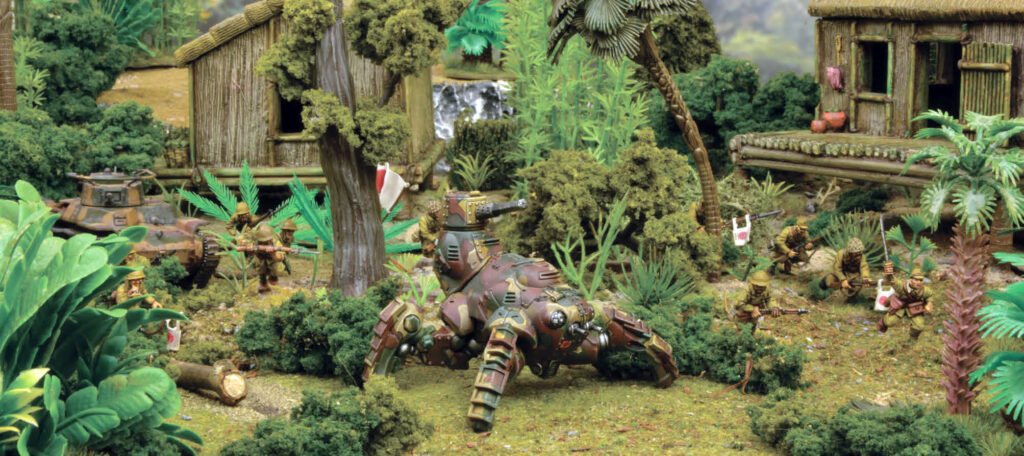

First deployed in the Ardennes offensive of early 1945, the Spinne was a simple vehicle – really no more than an armoured cabin and lightweight engine perched atop four spindly legs, with an open turret mounting a 2cm light autocannon. The quadruped design, chosen for speed and reliability, provided fantastic rough terrain performance, while the light armour protected the two-man crew from small arms fire. Designed for reconnaissance and harassment rather than frontline combat (as with the armoured cars it was intended to replace), the light autocannon was seen as perfectly satisfactory for self-defence and anti-infantry work. In the dense forests of the Ardennes, the Spinne units proved to be a nightmare for US forces, with their height allowing them to fire down into the American trenches, and their mobility making it almost impossible for US anti-tank forces to intercept and counter them. Nevertheless, the rushed development of the type led to a number of issues, particularly with the powerplant and incredibly complex gearboxes required to power each leg. These would be ameliorated to some extent in the subsequent ausf. B and C (Flamm) versions which would be deployed to good effect in Italy, but it was definitely an immature design.

By contrast, the US and British scientists took a rather longer path to the deployment of their first walkers, preferring to iterate upon their pre-war ‘humanoid’ design concepts due to the perceived utility of arm-mounted weaponry (and the potential of hand-enabled dexterity) in close-quarters firefights. The initial wave of Allied mechs were first deployed during the Battle for Brussels in August 1945, comprising the Coyote, Guardian, and Grizzly. The first two were based on a common chassis, the M5, with the Coyote being the machine gun-armed M5A2 initial production variant in service with both British and American forces, while the Guardian was a British modification mounting a flamethrower for urban clearance operations. A one-man affair, the M5 was in many ways almost a development of the heavy armour concept, as it essentially combined the roles of armoured car and infantryman into one package. Well-liked by the troops it supported, the M5 was nonetheless regarded as a difficult machine to operate, with an enormous workload for the single crewman, and this did limit its operational effectiveness somewhat. Used in a very similar role to the Spinne, it would go on to serve on all fronts throughout the war in the light recce role.

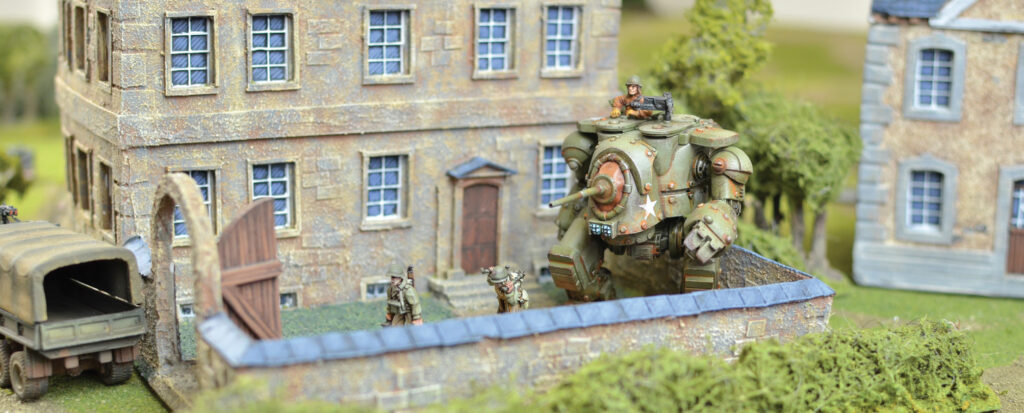

While the M5 series walkers proved satisfactory, Brussels also saw the debut of what would become arguably the most iconic Allied fighting vehicle of the ongoing war, and the first truly practical combat walker to see service – the M8 line of Medium Assault Walkers. Stemming from a seemingly simple request from the US Army to ‘take a Sherman and put it on legs”, the project had a difficult gestation, with numerous issues surrounding crew ergonomics and the installation of an unproven Rift-tech powerplant. Nevertheless, what eventually emerged as the M8A1 and A2 ‘Grizzly’ proved to have more than met the design specification. Mounting the combat-proven 75mm gun, .50cal heavy machine gun, and a pair of grasping fists, and well-armoured enough to stand up to frontline combat, the Grizzly swiftly became the preferred choice for close support in urban areas for US and British troops, while the chassis would soon be adopted as the basis for a number of other variants.

While the Soviet Union and Japan lagged somewhat behind in rift-tech development due to their geographical (and, in the case of the Soviets, increasing political) isolation, they too recognised the value of combat walkers. Using captured German and stolen US technology, Soviet engineers produced the Cossack, essentially copying the Spinne concept that had been used to such good effect against them on the open steppes of Eastern Europe but utilising the more advanced bipedal leg system to provide greater speed. Lacking some of the advancements that had been made on the Hedley-Kaye Principle, the Cossack suffered from a somewhat rudimentary gyro system which precluded the instalment of particularly heavy weaponry but was otherwise a perfectly serviceable light walker. In Japan, meanwhile, German rift-tech and scientific expertise were far more readily available, having been transported across the ocean in secret by U-boat. Seeking a replacement infantry support vehicle for their thoroughly obsolete series of tankettes, and having made significant advances in the field of servomotor and battery miniaturisation, Japanese engineers expanded on the quadrupedal concept of the Spinne to produce the Type 6 light walker, known to its crews as ‘Sasori’ (scorpion). A squat, highly mobile vehicle designed to keep up with advancing infantry over virtually any terrain, and equipped (in its infantry support configuration) with either a light anti-tank gun or compression cannon, the Sasori proved to be a dangerous opponent for Allied forces in the Pacific, acting as an effective ambusher against enemy armour, and providing vital covering fire for Japanese soldiers.

With the initial wave of light walkers having seen significant combat by 1946, and the Allied M8 series redefining what could be achieved with walker technology, the logical next step was, of course, to get bigger! With German High Command’s enthusiasm for enormous, armoured vehicles, it would unsurprisingly be the Wehrmacht who deployed the first of the new generation of heavy walkers. Designated the Schwere Panzermech II ausf. A (‘Thor’) and ausf. B (‘Zeus’), these gargantuan vehicles were first deployed in April 1946 in defence against the Allied Operation Grenade. Based on a common (and huge!) chassis, the Thor mounted a heavy howitzer for urban clearance operations against well-entrenched infantry, while the Zeus was equipped with an enormous 12.8 cm anti-tank gun, intended to be the last word in tank-hunting. Due to their sheer size, German scientists developed an unusual sextuple-leg arrangement, providing a very stable (albeit rather slow) firing platform. When first deployed, the Thor and Zeus sent shockwaves through Allied and Soviet forces, with rumours of ‘invincible mechs’ spreading like wildfire. The Herculean effort of Hauptmann Specht, commander of Zeus 212, in defence of a Rhine crossing point, well-illustrated the fearsome power of the type, but also revealed the inherent vulnerabilities of such a slow vehicle – artillery! On the Eastern Front, the Zeus quickly earned a similar reputation to that of the earlier Tiger I, punishing Russian armour at immense ranges, while the Thor became the terror of the normally stoic Soviet infantryman, with the threat of its howitzer often enough to convince even well-built defensive strongpoints to surrender. As German railgun technology matured, a version of the Zeus (classified as Zeus-X) mounting the colossal weapon entered service; its enormous hull providing more than sufficient space to accommodate the requisite battery of generators.

Desperate to counter this threat, the Soviets launched an all-out effort to acquire one of the new German super-weapons, eventually succeeding in capturing an intact Thor in mid-May 1946. The man of the hour, one Captain Gennady Provoroff, was immediately made a Hero of the Soviet Union, and promoted to General (quickly replacing one of the men purged from the faltering 1st Belorussian Front), and Russian scientists set to work reverse-engineering the design. Within a month they had a viable prototype, and by July the streets of Budapest shook to the tread of a vast (and very Soviet) machine – the Mammoth. A four-legged, multi-turreted behemoth, the Mammoth resembled nothing so much as a giant T-35 perched atop a quartet of Thor leg assemblies, and was intended for use as a mobile bunker in the harshest combat environments imaginable. Mounting a pair of howitzers and a trio of autocannons, the Mammoth was capable of laying down a withering barrage of fire in all directions, proving (despite its somewhat awkward appearance) a lethal asset in the confines of a city-fight. Mirroring the development of the Zeus, a variant (known as the Mastadon) was also produced mounting the tried and tested 122mm anti-tank gun in a single turret, and would go on to prove a dangerous adversary for its opposite number.

While the Germans and Soviets escalated dramatically in the tonnage of their walkers, the Allies chose to refine the proven concept of the M8 Grizzly. The first variant was the M8A3 ‘Tesla Grizzly’, a simple swap of the 75mm main gun and ammunition for a crackling Tesla cannon and associated generators. By 1946 a relatively mature weapon system, the Tesla cannon provided Grizzly platoons with the ability to engage enemy armour that increasingly outmatched the ageing 75mms and was usually fielded alongside a pair of M8A2s. A further development, again intended to provide greater anti-armour punch, was the M8A4, nicknamed the ‘Bruin’, which sacrificed the fists of the Grizzly for a pair of enormous heavy rocket racks. While losing the versatility and some of the urban utility of the fists, the Bruin was an effective and (relatively) low-cost upgrade that could be made to Grizzly units in need of greater firepower at field repair workshops, and many of the older M8A1s would be converted to A4 standard in 1946 and ’47. Other A1s would be rebuilt as Armoured Recovery variants, much-loved by combat engineer units for their ability to demolish buildings and barricades in moments. The M9A2 ‘Kodiak’ and British M9 ‘Hornet’ were born from the same requirement for walker-based anti-aircraft vehicles to accompany M8 formations. Both removed the 75mm gun to provide more space for ammunition, with the Kodiak utilising an arm-mounted autocannon battery, while the Hornet concentrated its firepower in the central torso and retained its fists – both would prove to be utterly devastating, both in their original role and when deployed against infantry and light vehicles. During this time, the Canadian Army also broke new ground for the Allies, deploying women to combat roles for the first time as walker crews, realising that their generally smaller stature made them ideal for such cramped conditions, and wishing to make best use of the thousands of women volunteering for more hazardous duty.

The US also made excellent use of their newly-developed repulsorlift technology to create a series of highly-mobile, jump-capable walkers from the combat-proven Coyote line. The M5A5 and M5A6 ‘Jackal’ series were intended to provide the US Airborne Firefly units with immediate light fire support on deployment, and as a counter to the Spinne and Sasori walkers in dense terrain. Lightly-armed in favour of speed, they formed the initial armoured punch of many US combat drops, but suffered badly against enemy tanks and walkers for want of any heavy armament. To provide airborne troops with more effective support, the M2 ‘Mudskipper’ was rushed into production, having been ordered without any prototypes being produced. Based on a stripped-down M8 drivetrain and basic chassis, and fitted with advanced repulsorlift and shock absorber systems, initial field tests revealed a disastrous flaw with the inertial guidance systems that led to several unfortunate losses before the system was corrected. Armed with a pair of light autocannons and a pair of heavy machine guns, alongside the ubiquitous fists, the Mudskipper made its combat debut on the Rhine in late 1946 to resounding acclaim. While British Airborne forces may have been reluctant to adopt repulsorlift technology for their paratroopers, they were keen to replace the Tetrarch (never a fully satisfactory compromise design) in the airborne armoured support role, and the 12th Battalion, Royal Tank Regiment was hastily redesignated as a jump-capable unit with the type, much to the dismay of some of its officers and men!

While the Allies had a clear advantage in medium walkers, the Coyote development line was seen as having reached its zenith with the Jackal, and the US Marine Corps desired a more versatile light scout walker with greater firepower to support beach-landing operations in the Pacific. The M3 ‘Pondskater’ was developed specifically to be deployed from the ubiquitous Landing Craft Infantry, mounting either an array of .30 and .50cal machine guns in the anti-infantry role (designated M3A2) or an M20 recoilless rifle (M3A5) for engaging light armour. A simple, rugged design in keeping with USMC doctrine, the M3A2’s lightweight design also made it suitable for glider-borne troops, and after its successful combat debut against Japanese forces was swiftly adopted by the US army, where it would largely replace the aging M8 armoured car in the light reconnaissance role in western Europe. Although virtually unarmoured, in the hands of a skilled crew it proved to be extremely difficult to hit, and exceptionally manoeuvrable in dense terrain, quickly becoming a prized asset to American commanders.

The widespread success of the Grizzly family led to a desire among German and Japanese commanders for a Panzermech able to match it in combat. Almost a year of feverish development incorporating the very latest Rift-tech produced the Panzermech III, commonly known as the ‘Heuschrecke’ (locust). This somewhat overdesigned machine incorporated a pair of autocannons, two fists (a first for German walkers), and either a light rocket system (the ausf. A) or medium anti-tank gun (ausf. B), along with repulsorlift capability and a number of advanced motive systems. Fiendishly complex to build and maintain, it was nevertheless a versatile and effective weapon on the battlefield, ideally suited to support fast-moving German attacks or bolster weak points in defence, and more than well enough armed to engage enemy infantry, tanks, and walkers alike. Japanese high command was desperate to acquire the Locust to give them a true frontline walker, and a license-production agreement was reached in late 1946. The Japanese Locusts deleted the repulsorlift and associated jump systems for decreased weight and improved mobility, and the fists were modified with agricultural attachments for better jungle-crossing ability.

The pinnacle of combat walker technology in early 1947 was arguably the British Walker, Combat, Heavy, W.11, more snappily referred to as the ‘Merlin’. The largest of the Allied walkers, the Merlin combined British research into artificial intelligence with the desire for heavier anti-tank weaponry to counter the threat of Zeus and Mastodon units. Initial attempts to mount the excellent 17pdr gun were unsuccessful, but the M7 3” gun (of which large numbers could be taken from M10 tank destroyer stocks) was successfully implemented as a suitable replacement. The most revolutionary aspect of the Merlin was its use of a single crewman, aided by significant AI-driven automation, for such a large vehicle. This allowed for far faster reaction times than a traditional crew and made the type absolutely lethal in a walker duel. Although on the bleeding edge of technological development, the Merlin soon gained a reputation as a durable machine (albeit one requiring very specialist maintenance), and the British Army ordered them in enormous numbers.

On The Table

With that exhaustive history of walker development done, let’s take a look at how they do on the tabletop battlefields of Konflikt ’47! Walkers fall into four categories – Scout, Light, Medium, and Heavy – and have a few interesting special rules that make them absolutely unique in the game. Firstly, their terrain-crossing ability is second to none, allowing them to bypass anti-tank obstacles, bocage, and the like with ease – this, combined with their 12” Advance and 18” Run movement values gives them the ability to get around the board quickly (and the jump-capable ones even more so!). This makes them the ideal ‘fire brigade’ units, going to wherever there is a problem and dealing with it.

In close combat, walkers have the Assault rule, allowing them to lay into enemy infantry and vehicles in hand-to-hand fighting. When they charge, enemy troops can only hit them on a 6, and they can bring a serious beatdown with two base attacks, plus another for each fist they have! This makes a walker like a Grizzly or Locust more than capable of wiping out an incautious squad or vehicle that gets too close, and the mobility we just described gives them an enormous radius in which they can do this. This forces your opponent to really be on top of their game positionally – one wrong move, and your walkers can pounce! Quite aside from beating up units with giant metal fists, most walkers also mount a concerning amount of firepower – even light walkers usually have more than the average vehicle, particularly machine guns and autocannons. This makes them ideal for anti-infantry work – the last thing an enemy squad wants to see is a Kodiak or Hornet drawing a bead on them, and this can be a powerful deterrent to your opponent getting their units onto objectives or implementing their gameplan.

That’s not to say that walkers are all-conquering, however! It’s important to be aware of their chief limitations – lighter armour, and (with obvious exceptions) a lack of really heavy weaponry. Of the two the armour should be your biggest concern. With an Armour value one less than their ‘equivalent’ traditional tracked tank (for example, a Medium Walker has Armour 8+ compared to a Medium Tank’s 9+), even the largest mechs can be surprisingly vulnerable if you aren’t careful, particularly to the kind of anti-tank weaponry commonly found in K47! Heavy and super-heavy anti-tank guns abound, whether towed or in the turret of a tank, and these can ruin a walker’s day very, very quickly. It’s normally not the best idea in the world for a walker to try and go toe-to-toe with a tank alone – make sure you’ve got something else in support to keep that tank busy! As for anti-tank guns… remember, they’re automatically destroyed if you manage to assault them! Use your mobility to your advantage, and make good use of available cover to stay safe until it’s time to go for the kill.

Mount up! Power up! Engage primary gyros – let’s go for a walk!

4 comments

Awesome article. Walkers and heavy infantry are what brought me into Konflikt ’47.

Great read and good to see more Konflikt 47.

so this means we are getting a Tesla Grizzly model soon, right? RIGHT? RIGHT!?!?!

So glad to see this awesome hame getting more support. It has so much commercial potential. I remember when the first starter boxes came out, Neal at the Warstore told me it was the hottest selling item he’d ever had. He couldn’t keep them in stock. But lack of support has let it flounder. I hope this means a resurgence.

Comments are closed.