In recent weeks we’ve been taking a look at the high-tech gadgets (and genetic aberrations!) that populate the tabletop battlefields of Konflikt ‘47’s weird war. This time, we’re examining one of the earliest of Rift-tech developments – infantry heavy armour! Let’s roll up our (metal) sleeves and dive right in!

By the time of the opening of the Rifts, all major belligerent nations of the Second World War had conducted significant experimentation with infantry body armour, seeking to reduce the number of gunshot and shrapnel deaths incurred, particularly in close-quarters combat. The Soviet Union had long issued its assault engineers with the simple SN-42 steel breastplate, which was reasonably effective but cumbersome and unpopular, and protected only the chest and groin, while the Allies had developed the so-called ‘flak jacket’ for their bomber crews and sailors. None of these designs were truly satisfactory in reducing combat casualties, although they were certainly better than nothing, but their weight and inconvenience often led to soldiers discarding them in favour of increased mobility and a reduced load. What was needed was nothing short of a modern suit of plate armour, strong enough to resist incoming fire but well-fitted and lightweight enough to not overly impede a soldier’s combat movement. Until the Rifts opened and the mysterious signals began to be deciphered, there simply was no such technology in existence.

Suit up – this is gonna get heavy…

Germany

The Germans, desperate to halt the Allied advance in the West and simultaneously drive the Soviet Union back in the East, were the first to introduce viable heavy armour into service. Known as Panzerharnisch 44 (a reference to the harness of the medieval knights featured so heavily in German propaganda), the earliest types saw service in June 1944 as the Allied forces pushed inland from the Normandy beaches. These examples were little more than crude exoskeletons with armour plating bolted to them, powered by a miniature rift-tech powerplant, and were halting and clumsy in their movements. However, their durability proved a powerful psychological tool, allowing the wearers to fight with far greater aggression and confidence than before, and filling inexperienced enemy troops with dread as their bullets ricocheted harmlessly off the sinister-looking suits.

Rapid refinements of the designs were in progress even as the prototypes were in action, with the subsequent Panzerharnisch 45 and the definitive 46 series introducing a vast number of improvements. By 1947, heavy armour had been rolled out en masse to a significant number of Panzergrenadier units, which became the preferred elite troops of the Wehrmacht, often used in what would be termed (with typical soldiers’ humour) ‘langsamer Blitz’ (slow lightning) attacks, grinding forward with significant armoured support to overwhelm enemy positions. Concealed beneath gasmasks and ballistic goggles, armed with the StG-44 assault rifle and the proven MG-42 light machine gun, and festooned with Panzerfaust and Panzerschreck anti-tank weapons, German heavy infantry soon gained a reputation as incredibly tough soldiers, capable of chillingly resolute advances in the face of murderous incoming fire.

The United States

With Germany deploying armoured infantry to such good effect, it would not be long before other nations followed suit. The USA, reeling from the heavy casualties suffered during D-Day and the numerous beach-landing operations in the Pacific, rapidly developed the Suit, Personnel, Armoured, M1 using lessons learned from captured German examples. A more mature and refined design, the M1 and subsequent M1A1 incorporated a number of significant improvements, most notably in the lighter alloys used in the armour plating, and the more advanced servo-motors powering the joints. This produced a significantly less restrictive suit, allowing almost a full range of normal motion, with tests demonstrating that a fit soldier could actually run, jump, and complete a standard US Army combat obstacle course while so equipped. Interestingly, US soldiers were initially reluctant to utilise the new heavy armour, nicknaming them ‘tin cans’. Rumours spread that the rift-tech powerplant’s emissions caused infertility, and that the armour was too slow to remove for a medic to save a wounded soldier’s life. The US Army put significant resources into debunking these myths, particularly in the form of educational films starring well-known actors (although the ‘tin can’ moniker proved unshakeable), and the first American heavy infantry units were ready in time for Operation Newport in Western Europe in April 1945.

While the operation was only partially successful, the new units proved their worth, particularly during the subsequent Battle for Brussels, where senior Allied commanders described their combination of protection, firepower, and mobility as worth its weight in gold. With the introduction of the M1A2 model in mid-1946, the US heavy infantryman was arguably the best-equipped in the world, with his suit boasting infra-red optics and a powerful arm-mounted assault rifle, and with the American industrial juggernaut churning out suits in their thousands, surrounded by plenty of comrades! From the freezing European winter to sweltering Pacific summers, they played a crucial part in the American war effort.

Great Britain

The British, traditionally rather unique in their approach to Rift-tech developments, watched the German and American experiments with great interest. While they could see the utility of heavy armour technology, they believed that the doctrine employed by the US was deeply flawed, and that instead of mass-producing M1A2 suits for widespread general usage, small numbers of much more heavily armed and armoured infantry should be used in precise tactical operations to overwhelm enemy strongpoints that would be impossible to storm with normal infantry. This led to Project Round Table, and a number of prototype suits were developed. The Bedevere and Percival suits proved the basic viability of the concept, using metallurgical techniques drawn from Britain’s warship industry, augmented with Rift-tech principles, ultimately leading to the Galahad Mk I production model. Boasting an arm-mounted light machine gun developed from .303 Browning aircraft guns, and monstrously thick armour plating, the Galahads virtually turned a man into a light tank.

While slow and cumbersome, live-fire tests on Cromer beach proved them more then capable of shrugging off sustained small arms fire at close ranges (whilst terrifying the local Home Guard commander, who had to be personally cabled by the Prime Minister before he could be convinced that the Germans were not invading!). The complex alloys used in the armour plates made the Galahad suits prohibitively expensive for true mass production, but by converting a number of shadow factories to their manufacture allowed for a reasonable number to be built and issued, with production ramping up throughout 1946. Deployed to Europe initially in small quantities with the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, the Galahad suits quickly became popular amongst the British forces, greatly reducing the casualties taken when storming German bunkers and dug-in positions. Their usage was less common in the Far East, where the humidity made the suits almost unbearable, but some were retained for use against well-fortified Japanese-held islands.

Japan

The Japanese themselves quickly recognised the need to counter Allied heavy armour, knowing that it would only be a matter of time before it would be deployed in greater numbers to the Pacific theatre. As part of their ongoing technological exchange with Germany, Japan received the full technical package for the Panzerharnisch prototype series, which they combined with their own research into miniaturised electronics and servomotors. The highly complex technologies involved led to significant issues in development, and a number of unfortunate testing fatalities resulted in what were concerningly titled ‘uncommanded overmobility incidents’, and the entire project was shelved for almost six months, before being revisited by a brand-new design team. This new study resulted in the Sentou-Gaikokkaku (battle-exoskeleton) – a lightweight design that sacrificed protection for mobility (considered a high priority in the dense Pacific jungles), and took clear design cues from the accoutrements of Edo-period samurai.

Mounting submachine guns and light machine guns, alongside the new compression rifles, as well as small-calibre grenade launchers and wicked single-edged combat blades, the battle-exoskeleton proved a lethal and deadly short-range asset in close-quarters fighting. While less numerous or well-armoured than their US and British counterparts, their agility and veritable arsenal of weaponry, combined with a fearsomely intense training regimen, made them a significant threat if they could approach to short range undetected. Against conventional infantry, they were a pure terror, and Allied soldiers soon learned not to advance through dense underbrush without first ‘brassing up’ the foliage with machine-gun fire.

Further development of both equipment and doctrine led to the Totsugeki-Gaikokkaku (assault-exoskeleton), which traded some of its firepower for increased melee capability. Worn by some of the most fearsome hand-to-hand combatants of the entire conflict, they were deployed where a breakthrough could only be achieved by sudden, ferocious violence, and were rightly feared by all Allied soldiers. While somewhat limited by Japan’s industrial capacity, the exoskeletons were given the highest priority for production, and by late 1946 were considered a key component of every brigade or larger formation.

The Soviet Union

While the Japanese heavy armour efforts focussed on the high-tech developmental possibilities brought about by the Rifts, the Soviet Union sat firmly at the other end of the spectrum. Taken somewhat by surprise when the first German and American heavy armour appeared, Soviet designers were forced to scramble to keep up, despite lacking many of the Rift-tech advancements possessed by their enemies. Rushed into production in great numbers, the original Mk I suits were simple to the point of crudity, with their only really advanced system being a reverse-engineered copy of the Panzerharnisch powerplant. Bulky, heavy, and immensely uncomfortable to wear for any real length of time, they nonetheless provided significant protection for the wearer and when used in significant numbers were a potent force on the battlefield.

Interestingly, the Soviets considered their heavy infantry units primarily as anti-tank assets, and armed them with a simple but innovative dual weapon pack, comprising a short-barrelled PTRS-41 anti-tank rifle mounted alongside a stripped-down PPsH submachine gun. This provided thoroughly acceptable anti-infantry firepower, and while the anti-tank rifle was by 1945 more or less obsolete as a primary anti-tank arm, concentrated fire from a unit’s worth of them was still a threat that any vehicle commander had to take seriously, lest they find their mounts disabled by dozens of minor impacts. Given the lessons learned in the bitter crucible of Stalingrad, hand-to-hand combat was also considered a priority, and powered claws were incorporated into the suits, capable of crushing metal and shearing through flesh and bone. These proved rather unreliable, and many soldiers resorted to carrying knives, clubs, or even sledgehammers as makeshift melee weapons.

As 1946 wore on, and Soviet scientists gained access to more and more Rift-tech, a full redesign incorporating the lessons learned from operating the Mk 1 suits was undertaken. Retaining the successful dual weapon packs and proven powerplant, the suits were extensively redesigned for increased manoeuvrability, reliability, and pilot survivability. While the Mk I remained the standard equipment of the Guards Heavy Infantry regiments by 1947, the Mk II suits were entering full-scale production and beginning to replace their predecessors on the front lines.

Italy

The final nation to make significant use of heavily-armoured infantry was the split state of Italy. As both Germany and the Allies poured resources into the fascist ENR and co-belligerent ECI respectively, it was recognised that heavy armour would be a vital component of operations in the often-difficult Italian terrain.

The ECI became something of a testbed for the British Galahad programme, with the elite Bersaglieri light infantry converting (somewhat ironically) to the type in order to serve as the spearhead of close assault operations. The Galahad was selected over the US M1A2 for its greater protection, and British scientists would spend significant time attached to the Bersaglieri formations gathering data and trialling minor improvements. One of the most obvious was the modification of the helmet for improved facial protection, taking inspiration from ancient Roman gladiatorial equipment in an attempt at producing an even more psychologically intimidating suit!

On the side of the Axis, the ENR received a unique and interesting product of the German heavy armour family, the Panzerharnisch 46(i) ‘Zenturio’. Specifically designed to invoke the silhouette of a Roman Centurion, these suits were deployed at the level of one company per battalion as a rapid reaction force to counter enemy assaults or exploit breakthroughs, and the Italian Zenturio operators proved to be some of the most fanatical adherents to the Axis cause anywhere in the world. Armed with assault rifles and lightweight ballistic shields, they engaged in a vicious private war with their Allied counterparts on many occasions, and earned the respect of friend and foe alike.

Heavy Armour In Konflikt ‘47

On the tabletop, the many national variants of heavy armour have a wide variety of capabilities and weaponry, but as a general baseline you can expect Tough, Veteran infantry mounting a significant amount of short-range anti-infantry firepower. With the ability to shrug off small arms wounds on a 5+, they provide an excellent ‘hard core’ for any force, able to soak up incoming enemy fire as they move across the table, and dish it out in return. Many variants are Slow, so some clever tactical handling is required, but these also tend to have Resilient, meaning they are only wounded on a 6! Regardless of specifics, as a general rule heavy infantry excel when up close and personal, particularly when facing their unarmoured counterparts – try and force a short-range shooting engagement which you’re likely to win. Against other heavy armour or genetic monstrosities, your heavy infantry will be ideally placed to slug it out and prevent them running rampant through your more vulnerable troops, making them (in my opinion) a vital component of any army. The only thing they really struggle against are big, nasty vehicles, but hey, that’s what you’ve got your own tanks and ‘mechs for!

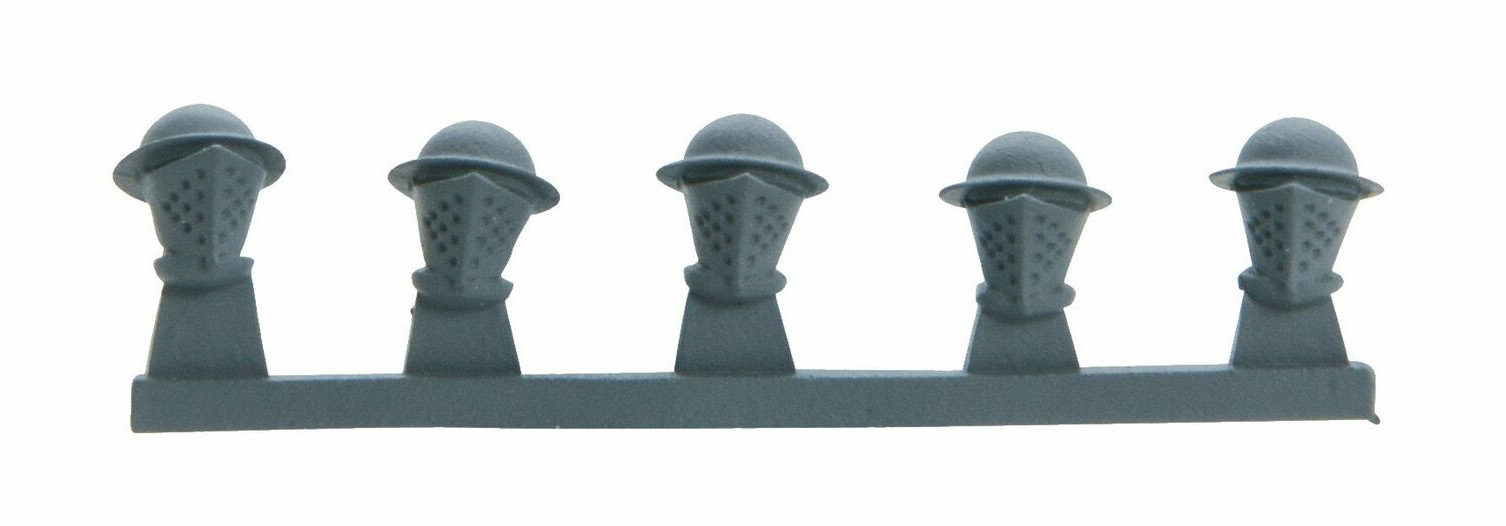

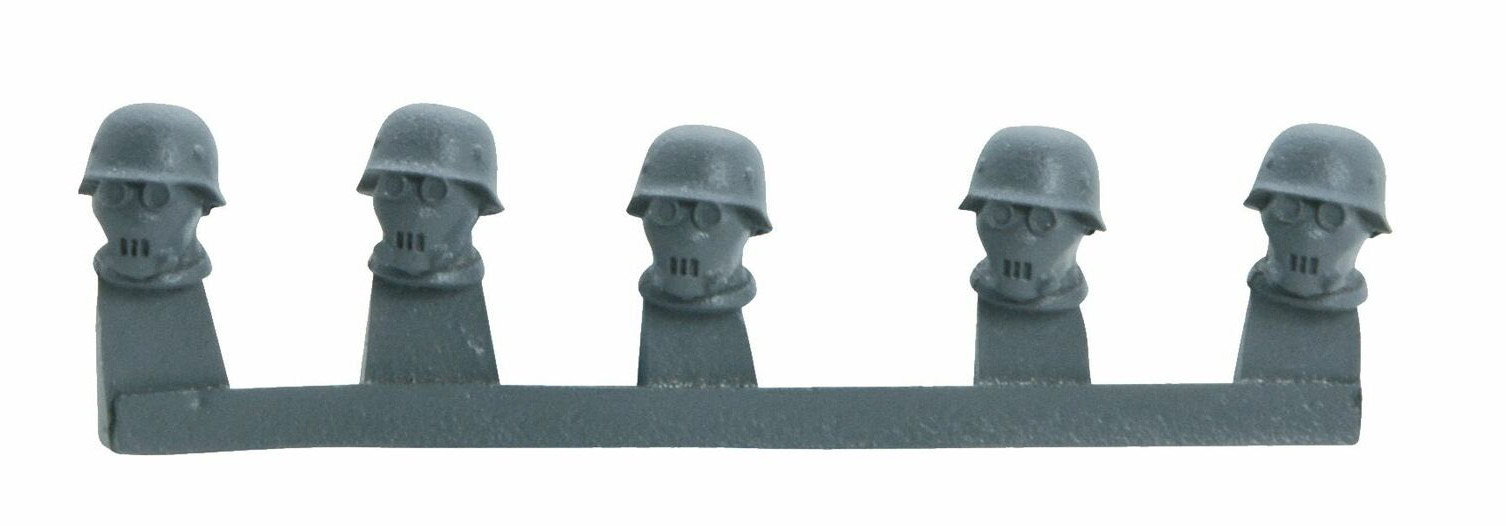

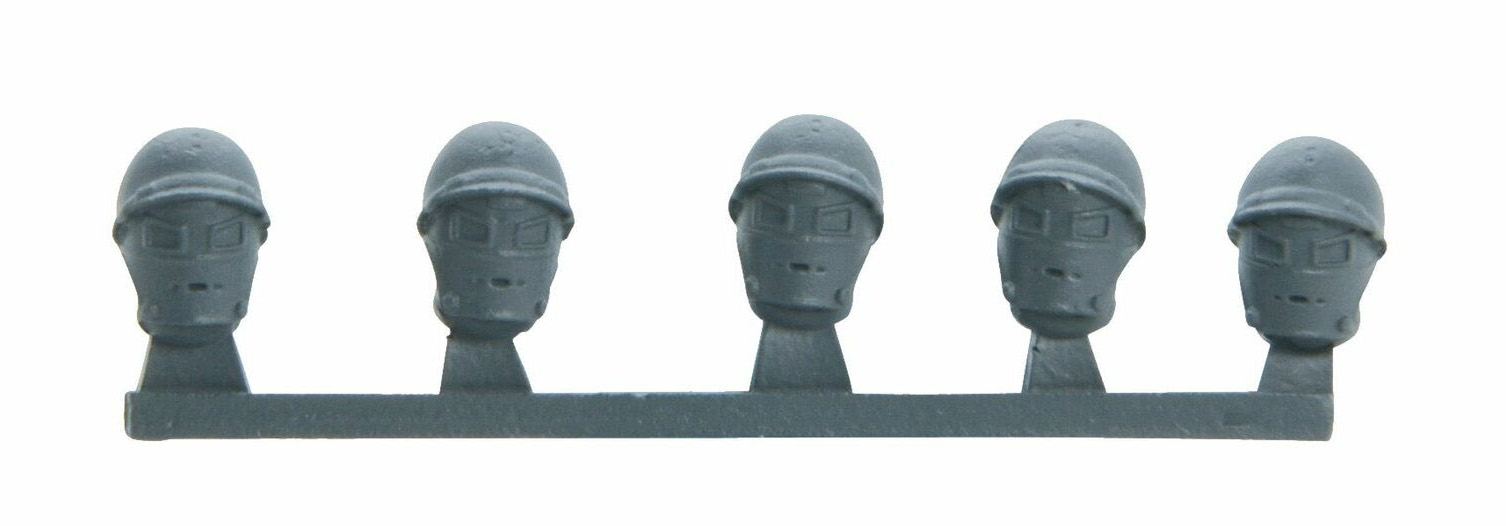

Heads Up

Make your Konflikt ’47 Heavy Infantry stand out on the tabletop with variant head options!

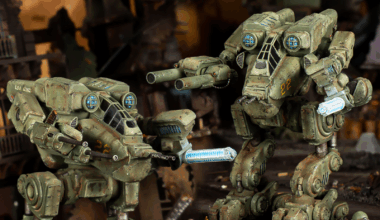

Here are some examples of some of them in use, painted up by our own Darron Bowley:

4 comments

Great article!

I absolutely love Konflikt 47, and I’m planning on adding some Heavy Infantry to my German force, so this article couldn’t have come at a better time!

This is awesome lore, think I’ll have to do that British Galahad army now!

Typical “cheaty” British by Warlord Games. Why does a German Heavy Infantryman with an MG need a loader, but a Brit doesn’t? Having been a machinegunner, it seems ludicrous that a man with an LMG attached to his arm, can somehow reload one-handed. Why don’t these Brit machinegunners suffer a penalty for not having a loader?

Comments are closed.