Called Getae by the Greeks and Daci by the Romans, the people living north of the Thracians gave their name to a region whose exact extents varied over time. Dacia lay around the Carpathian mountains, north of the Danube and extending at times all the way to the Black Sea. Sharing a common ancestry with the Thracians, the Dacians were less influenced by Greece and Persia, but frequently raided by steppe people including the Sarmatians. Some Sarmatian groups were allied with the Dacians at times, notably in wars against Rome.

The Ancient Greeks referred to the people dwelling northeast of Dacia as Scythians and named the vast steppe lands they inhabited as Scythia. The Scythians were not a single unified people but a confederation of nomadic tribes who wandered the steppes. They were generally peaceable in nature, but some members of their culture were willing to hire out as mercenaries. Possibly as a result of service in far-off theatres of war, the group known as Sarmatians came to prominence in the eastern end of Scythia.

They were far more warlike than the Scythians in general, worshipping a god of fire rather than the nature gods of the Scythians. The Sarmatians became the dominant force in the steppe lands and pushed into Europe where they came into conflict with the Roman empire. They were politically adept and quite willing to form alliances with the Germanic tribes of eastern Europe or the people of the Balkans, such as the Dacians.

Military Service

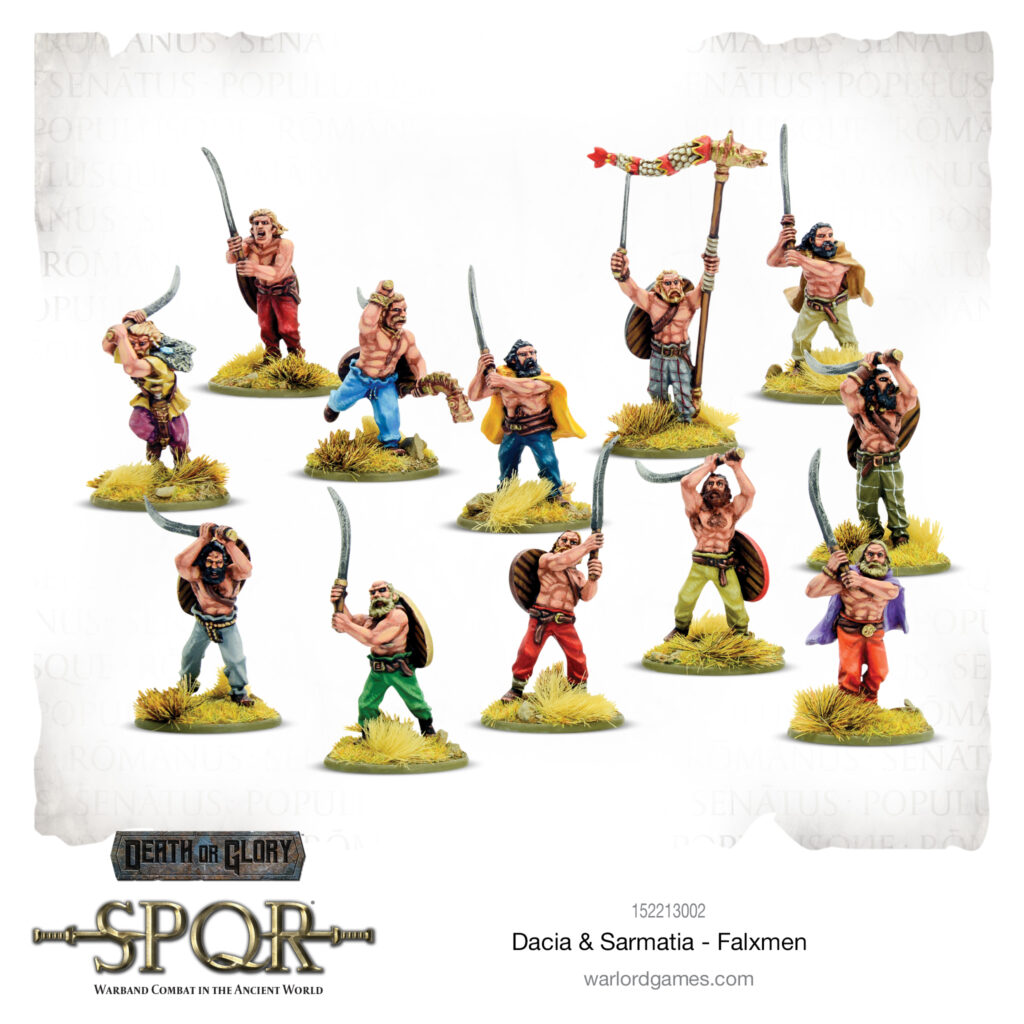

Sarmatian and Dacian military service was tribal in nature, with groups led by a charismatic individual and armed with what was available. Dacian infantry often included a mix of men armed with spears or the falx, a weapon with a curved blade that was sharp on the inside edge. Short-hafted falx (known as sica) were used by some warriors, but for the most part it was a two-handed weapon used without a shield.

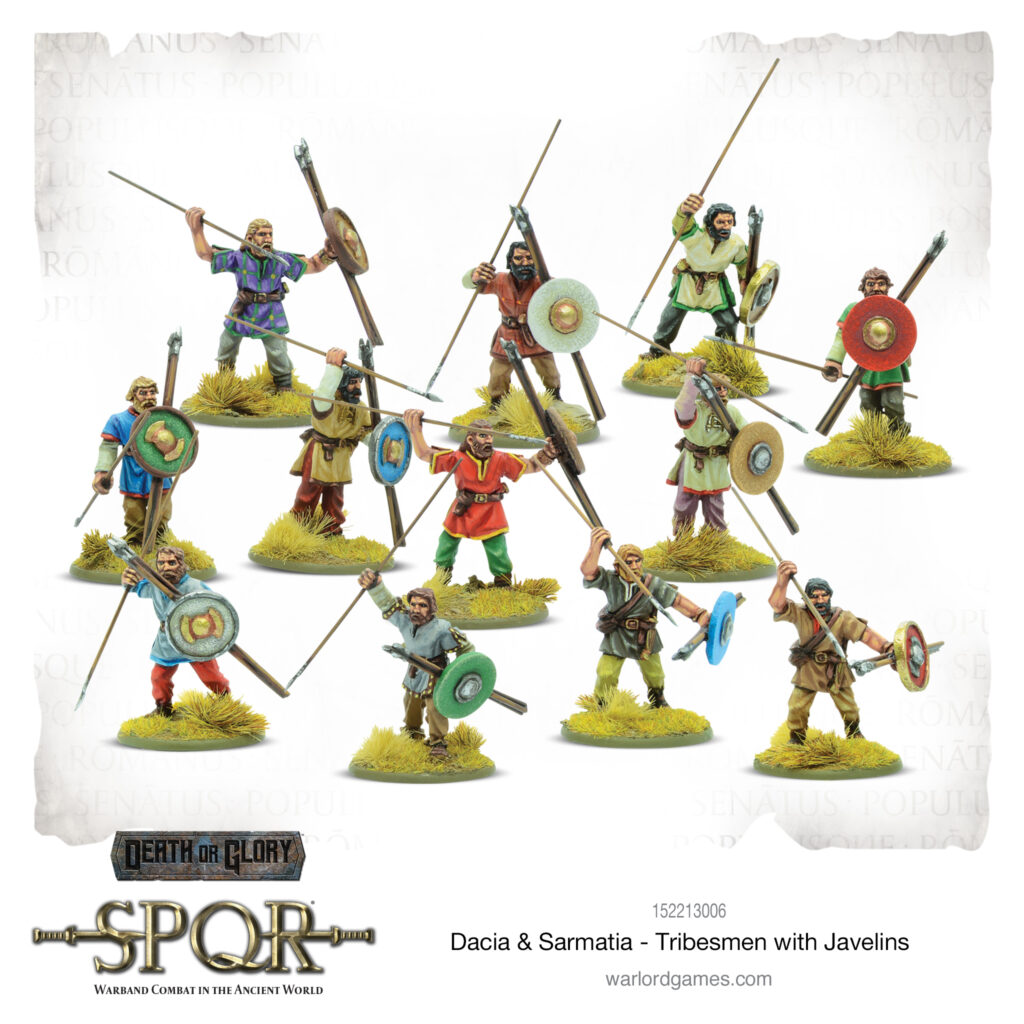

The Dacians also fielded archers but favoured a style of combat similar to other tribal peoples. Members of a warband would throw javelins before closing for hand-to-hand combat, fighting in loose groups that could advance or retire quickly as they were unencumbered by armour. Helmets were worn by some warriors, but on the whole Dacians relied on shields, mobility and their falxes.

For their own part, the Sarmatians had a militarised society and were willing to fight at the slightest provocation. Some tribes allied with the Dacians, some fought against them, and others squabbled among themselves or raided whenever there were rich pickings. Early in their history they wore light armour of leather and used wicker shields. This was replaced by heavy scale armour protecting horse and rider.

A Sarmatian cavalryman was equipped for skirmishing with the bow and close action with sword and lance. The latter was often used in both hands, without a shield. Those with lesser protection might skirmish with light spears that could be thrown or used as a lance, but Sarmatian warfare was very much a matter of getting stuck in with hand weapons. Cavalry did not drill in complex manoeuvres, though individuals were accomplished horsemen who may have been riding since before they could walk.

Appearance and Equipment

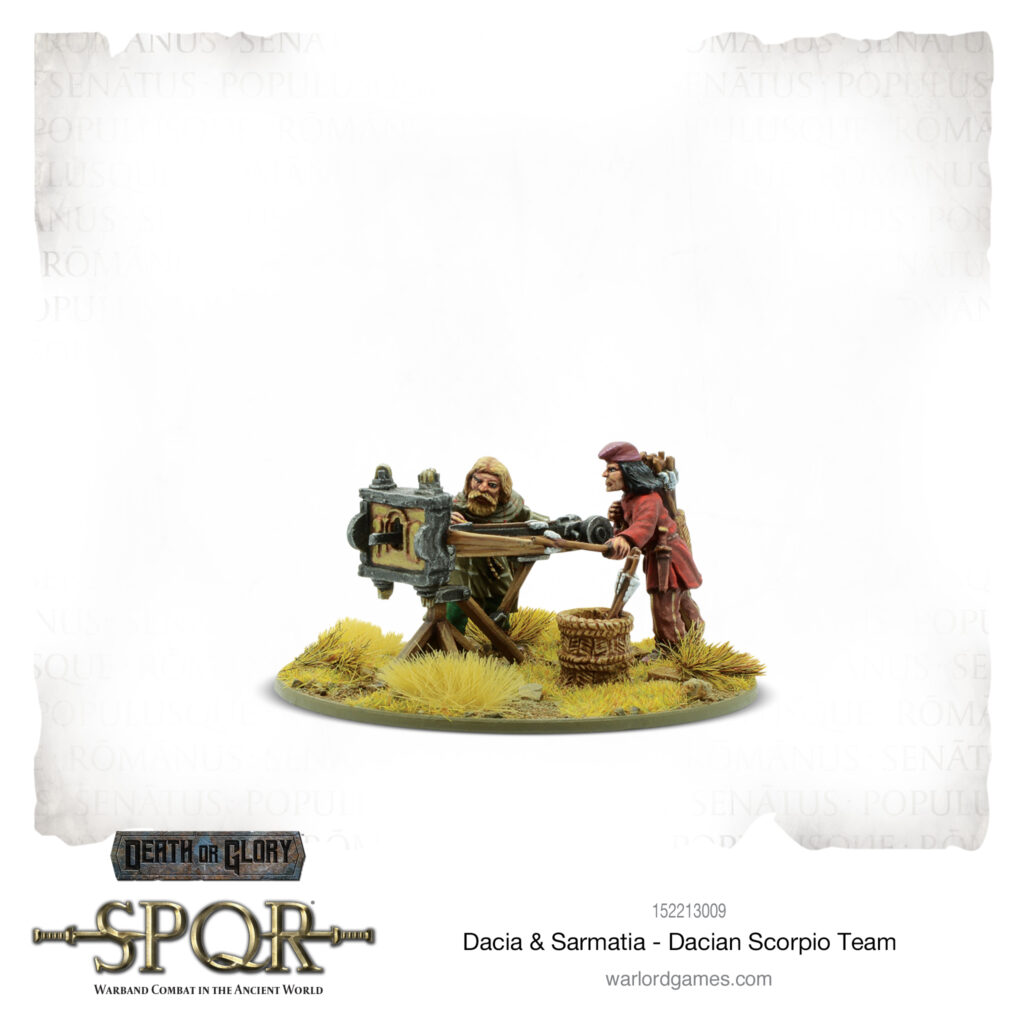

A Dacian and Sarmatian force is an alliance of very different warriors. The Dacian infantry component is a typically ‘tribal’ force with a mix of weapons and clothing styles in each group. Some individuals, particularly leaders, might have Greek or Persian style equipment – and some may have acquired gear from downed Roman soldiers.

The Sarmatian component will be more uniform since their armour was made to standard patterns. This does not mean they will be in neat lines like well-drilled cavalry, however; Sarmatian horses were generally small but tough and well-behaved, but that did not preclude some riders being out of position. Indeed, warriors were prone to pushing forward, eager to charge at the enemy, which would lead to formations being somewhat disorganised.

A leader might spend more time trying to herd his men together ready for a concerted charge than urging them on. Lighter troops – both Sarmatian and Dacian – were likely to be even less uniform in appearance and dispositions, with archers and javelin throwers spread out in open order that might border on complete dispersion. In action, they would clump together or move apart as the need and commands of their leader directed, but overall warfare was a rather informal business for such men, and the appearance of a warband should reflect this.

The Dacian & Sarmatian Warband

A warband comprising both Dacians and Sarmatians is immensely flexible, possessing both solid infantry and some of the finest cavalry the Ancient world was to ever see. So long as each side can be integrated with the other, the warband will be able to face any enemy with an immediate advantage, even the legions of Rome.

A warband of Dacians & Sarmatians is one of two halves – on the one side, a horde of bloodthirsty infantry willing to hurl themselves at an enemy and, on the other, superb cavalry that can outmanoeuvre and smash the enemy in equal measure.

Whether your Warband is composed of Dacians or Sarmatians, it will strike hard and fast but may lack the implacable staying power of a Roman Legion. Take advantage of your manoeuvrability and attack quickly before retreating before your enemy can grind you down.