While the French ‘heavies’ are by far the most celebrated cavalry of the Napoleonic Wars, there can be no doubt that the most splendidly uniformed (and least disciplined) were the British light cavalry – the hussars and light dragoons. Mounted on the finest horses available, gorgeously equipped, and with a reputation as dashing dandies, these light horsemen performed a wide number of roles in Britain’s armies and when led well (sadly this was uncommon) were capable of significant feats of arms.

The light dragoons were formed during the 18th Century primarily as a patrolling and scouting force, but also over time acquired a reputation for courageous and aggressive charges. Relatively late to the party, the British Army converted a number of these regiments to hussars, adopting what was at the time the absolute pinnacle of European military fashion. While differing wildly in uniforms and reputation (with the glamour of the hussar regiments serving as an irresistible lure to wealthy young men seeking a military career), they filled much the same role on and off the battlefield. Armed with sabre and carbine, they performed the often-tedious duties of strategic reconnaissance, scouting ahead of the main force and providing pickets and sentries to guard against surprise attacks. On the battlefield, they were mostly tasked with outflanking and harassing enemy units, while preventing their opposite numbers from doing the same. At the end of a battle, they really came into their own, using their mobility to run down fleeing units and prevent the enemy from regrouping and withdrawing in good order. Such use would prompt Napoleon himself to famously declare that no battle could be truly concluded without cavalry.

The primary armament of the light cavalryman was the Pattern 1796 light cavalry sabre (shown below), a vicious curved blade designed purely for cutting (in contrast to the cut-and-thrust heavy cavalry sword of the same year) and capable of inflicting horrendous wounds. Lacking the brute weight of the heavy cavalry sabre, they were nonetheless effective weapons. Having handled several personally (as a very mediocre swordsman), I certainly wouldn’t want to be anywhere near the business end of one! Reflecting their origin as mounted infantry (the more ‘proper’ term for a dragoon) they also carried carbines, and although they were often not carried into pitched battles, our plastic boxed set depicts them so armed – a little extra firepower never hurts.

The light dragoons, being the less ‘fashionable’ of the two types, were nevertheless splendidly attired in a smart blue tunic and white or grey breeches, and prior to 1812 wore the ‘Tarleton’ helmet, styled after ancient examples, thereafter replacing it with the simpler (but less spectacular) shako. The hussars meanwhile may be one of the primary reasons that the uniforms of the Napoleonic Wars are remembered as so outrageously decorative. Outfitted ‘Hungarian fashion’ with their dolmans (tunics) and pelisses (a kind of short jacket worn over one shoulder) dripping with braid and lace. Similarly gaudy were the ‘busby’ fur caps they wore, though some retained the rather more pedestrian shako. Uniquely for the period, moustaches were mandatory for British Hussars – presumably those of us without the genetics for excellent facial hair would have been issued some horsehair and glue!

On an individual level, the British light cavalryman was better equipped and far better mounted than his French counterpart. It was likely that he was a better pound-for-pound swordsman and horseman, and at least as determined and motivated. As a unit, however, the near-universally held opinion was that the British cavalry were far inferior in matters of mass drill and discipline (this does not include the King’s German Legion (KGL) light cavalry, who were highly regarded by friend and foe alike). Arguably the chief issue plaguing them was the poor standard of leadership they suffered under. This can be traced in the main part to the system in place in the British Army at the time, whereby officers’ commissions could be purchased rather than earned by any merit. Rather than receiving any formal training, they would be expected to learn the fundaments of their chosen profession ‘on the job’. This inevitably led to a situation where men were being led by officers unfit for command, many of whom neglected their units’ training. Others were concerned solely with battlefield glory, leading to a number of ill-advised charges and pursuits throughout the Napoleonic Wars for which the British cavalry suffered greatly. Despite this, there were dedicated and capable officers, most notably Major-General Sir John Le Marchant who went to great lengths to reform the army’s leadership, including founding the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, before dying at his moment of triumph at Salamanca.

In spite of their often-lacklustre leadership, when unleashed at the charge, the light dragoons and hussars could achieve excellent results against far heavier opposition. At Sahagun and Benevente in the Peninsula, they were able to handily defeat their French opposite numbers, winning much glory for their often-controversial commander, Henry Paget (later to become the Earl of Uxbridge). By Waterloo, Wellington had learned to keep his cavalry commanders on a short rein, and the light horsemen played a much-reduced role when compared to the death ride of the British heavies. Two regiments of light dragoons under Dornberg did engage with French cuirassiers, but were driven off by the armoured Frenchmen, with Dornberg himself badly wounded.

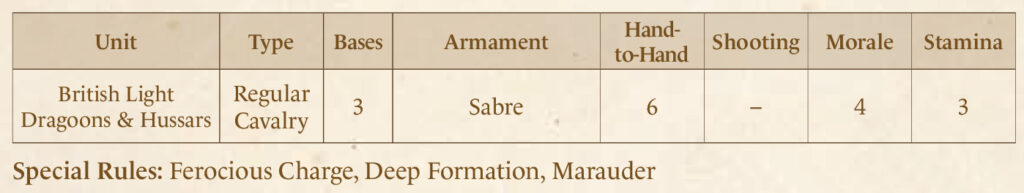

On the Epic Battles: Waterloo tabletop, we represent both hussars and light dragoons with the same profile, as the only real difference between them was the relative fanciness of uniform. With a respectable Hand-to-Hand value of 6, they can certainly cause plenty of mischief against infantry and cavalry alike, especially with their Ferocious Charge rule letting them re-roll all failed attacks in the first round of a combat where they charged or counter charged. As befits reconnaissance specialists, the Marauders rule allows them to ignore the usual penalties for being far away from their brigade commander when making order checks – perfect for making sure your rapid flanking manoeuvres go off without a hitch!

Also included in the plastic boxed set is a 3-gun battery of Royal Horse Artillery 9pdrs. Wearing the splendid Tarleton helmets, these blue-clad gunners add excellent mobile firepower to any force, without compromising on the all-important ‘style factor’ of their cavalry compatriots.

Don your gayest apparel and draw your sabre! We ride for death or glory!

1 comment

Why do the light dragoons have two different styles of shako? I have separated mine into different units but the box illustrations show them intermixed. Not a big deal, just curious.

Comments are closed.