One of the main reasons to maintain a navy is to deny use of the oceans to the enemy, preventing the movement of industrial goods and materials, troops and supplies. Commerce raiding formed a critical part of the strategy for some nations, and indeed represented the Axis’ best hope for victory over Britain. That victory was almost achieved, while in the Pacific US submarines gradually starved Japan of raw materials by much the same methods.

Preventing attacks on defenceless merchant ships is the other main role of the navy, and it was here the war was fought, day in and day out, by the humble corvette, frigate and destroyer escort, and later by escort carriers. These vessels battled the submarine threat for the duration of the war, and at times were forced to do what they could against a major surface raider, usually resulting in being sunk.

There were, however, other ways to defend merchant ships, or to give them a measure of self-protection capability. Grouping ships into convoys meant there was more expanse of empty ocean out there – hopefully raiders would not even find the convoy. It also made escorts more effective, but in the event a convoy was hit by a surface raider such as a heavy cruiser or battlecruiser, the concentrated target would be devastated in short order. Nevertheless, the convoy system helped a great deal.

Other measures included mounting a few light guns on merchant ships, often with army or navy reserve crews. While a couple of 4-inch guns in open mounts would be no use against a serious warship, they might be able to deal with a submarine. Many submarine attacks were carried out on the surface with guns, in order to save torpedoes. This practice became dangerous and Q-ships (armed merchants with concealed weapons) were deployed. Revealing her armament at the last second, a Q-ship could quickly sink a submarine if it could be lured in close enough to the ‘defenceless’ merchant. This was one reason why unrestricted submarine warfare was the only effective strategy.

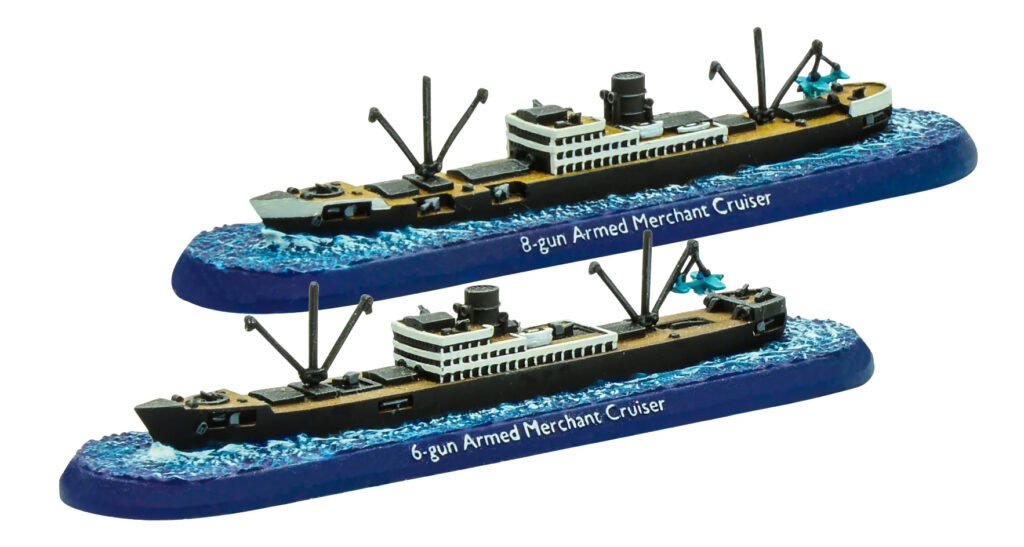

Armed merchant ships could also function as raiders. Germany made extensive use of such vessels, with mixed success. Even less successful were Armed Merchant Cruisers created by adding thin armour plate and a few guns to a liner or fast merchant vessel. Big, slow and horribly vulnerable, such vessels were no match for a real warship but were deployed for lack of anything better.

Overall, merchant ships were vital assets that had to be protected – or destroyed – as part of a warfighting strategy rather than combat assets. They might have been able to put up some anti-aircraft fire or even engage a surfaced submarine with guns but, faced with any serious threat, they were helpless. It would fall to the escorting ships (usually destroyers or the occasional cruiser) to defend them until either a heavy covering force could come up in support or the merchants could make their escape. Some of the most heroic, and worst mismatched, actions of the war took place in defence of convoys of merchants or troop ships.

The Atlantic Lifeline

The convoys voyaging across the Atlantic were Britain’s lifeline for the whole war. Without them, Britain would fall, and quite likely, the entire Allied cause with her.

At the onset of war, it was perceived by both sides that large ships, such as Germany’s pocket battleships, were the main threat to shipping. How wrong they were. The rise of the U-Boat, the radio communications that allowed them to quickly assemble as the infamous Wolfpacks, and after the fall of France, ease of accessibility from Atlantic ports quickly made the U-boats the dominant threat. Between September 1939 and December 1940, almost five million tons of merchant shipping was sunk, leading to U-boat crews to christen this period the Happy Time. It was only with the development of radar-equipped-aircraft that signed the death knell of the efficacy of the U-Boat, though the submersible menace continued to plague Allied shipping in significant numbers until May 1943, following a significant battle involving the convoy designated ONS 5.

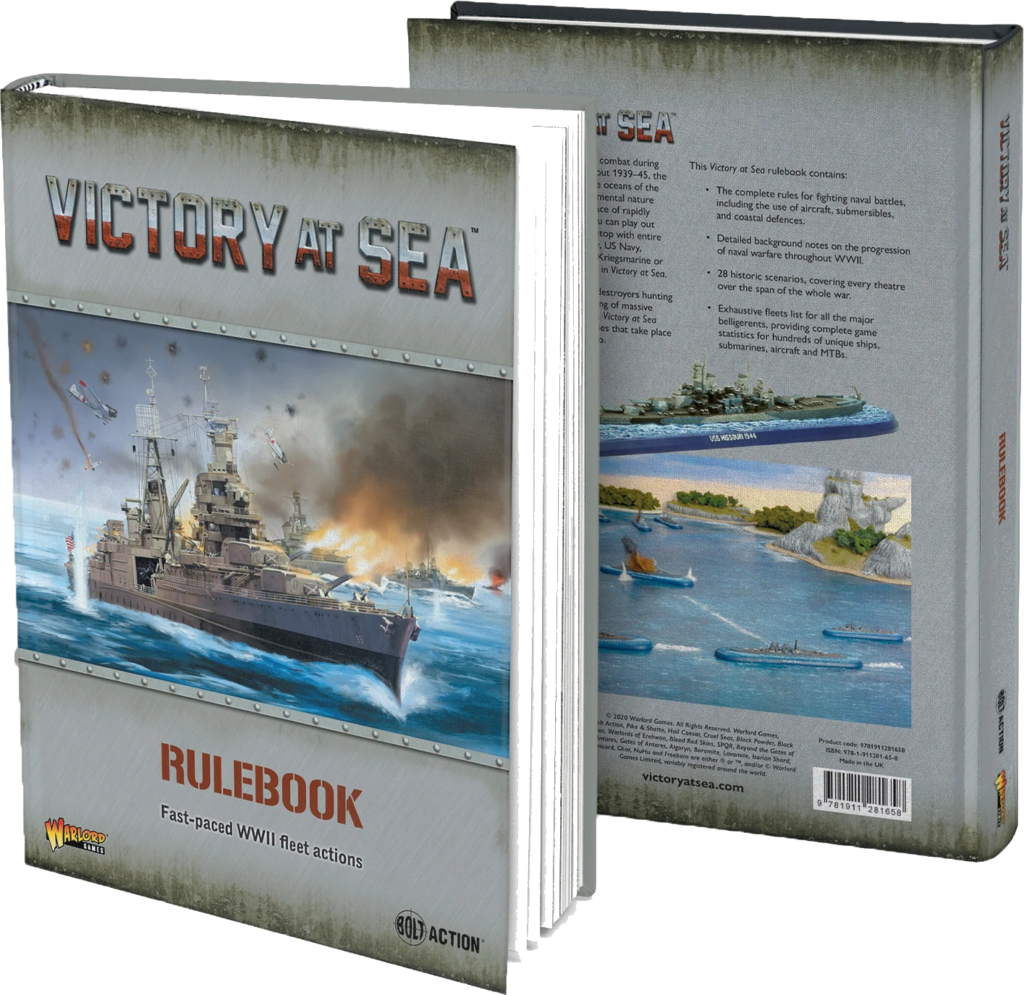

To best replicate these types of battles in Victory at Sea, refer to the Convoy scenario on page 65 of the Victory at Sea rulebook. This is one of the Submarine specific scenarios, involving one player fielding only civilian vessels, whilst the attacker fields only submarines, using the dedicated special rules in the immediately preceding section. This is perfect to replicate the convoy battles of the Atlantic or indeed those in any other theatre of the war.

The rulebook also includes exhaustive fleet lists for all the major belligerents of WWII, providing game statistics for hundreds of unique ships, submarines, aircraft and MTBs.

Submarines are available for every national fleet currently available for the game (boxed along with MTBs in most cases – providing even more variety and challenges for a burgeoning Victory at Sea fleet.