Prior to Battle

Seeking a decisive battle, the Imperial Japanese Navy began an operation against Midway Island in June 1942. If the island could be occupied, it would serve as a base to operate against Pearl Harbor and also help anchor the extended defensive perimeter needed to prevent a recurrence of the Doolittle Raid. Believing that the USS Yorktown had been sunk at the Coral Sea along with USS Lexington, Japanese planners thought they had a strategic advantage in terms of carrier strength. An attack on Midway would draw out the US carrier force into a one-sided battle that could only end with its destruction.

In fact, USS Yorktown had been made battle-worthy in an incredible three days and was available to join the US fleet headed for Midway. This brought US aviation strength up to three fleet carriers, plus the aircraft based at Midway for a total of 360 aircraft. Ranged against them was a formidable IJN force of four fleet carriers plus cruisers, lighter carriers and several battleships, including the huge and powerful Yamato. Japanese aviation strength was some 248 planes. The IJN also deployed 20 submarines as scouts and in a patrol line that would hopefully be able to ambush US ships.

Part of the Japanese force was detached to the north, threatening the Aleutian Islands in the hope that some elements of the US fleet would be drawn off. In the event, there was no response to this move, which deprived the IJN of part of its force rather than weakening its opponents. Likewise, the submarine patrol line failed to intercept the US fleet and inflicted no damage.

The Japanese fleet was sighted by US aircraft from Midway as it approached, and a strike was made by B-17 bombers which caused no damage. A followup strike by flying boats succeeded in torpedoing a transport vessel. More importantly, the US carrier force had access to good reconnaissance information from these aircraft, whereas the Japanese commanders did not know where the US carrier force was.

Attack on Midway and the First US Air Strike

The first Japanese strike arrived over the Midway Atoll around 0600 and was met by a rather outmatched air defence force. US fighters came off worst in engagements with Japanese Zeros and failed to inflict much damage on the strike force. Serious damage was inflicted on Midway, but not enough to ensure a successful invasion by Japanese land forces.

At 0700, the first US air strike found the Japanese carrier force and was mauled first by the defensive fighters and then by anti-aircraft fire. After suffering tremendous losses for no gain, the survivors of this attack retired towards Midway. This attack did, however, convince the Japanese commanders that a follow-up strike against Midway would be needed, which would in turn influence the outcome of the battle.

The order was given for the Japanese aircraft to be armed with bombs, suitable for land targets, and as further land-based strikes arrived the necessity of putting Midway out of action seemed ever more apparent. Then, at 0740, a report arrived of US carriers in the vicinity. The Japanese first strike aircraft were returning, low on fuel, and had to be recovered before the strike aircraft could be rearmed with torpedoes to attack the US carrier force. This operation was further delayed by strikes from the US carriers which suffered massive losses for no hits.

Caught Vulnerable

These delays meant that the Japanese carriers’ decks were packed with aircraft and, worse, there were bombs on deck which had not been taken back to storage in the hurry to rearm for an anti-shipping strike. At this point, a force of US dive bombers arrived over the IJN carrier fleet. These bombers had struggled to find their targets and arrived late, at a point when the massacre of the earlier strikes had drawn the defensive fighters down low and expended most of their ammunition. The fleet was also in disarray due to violent evasive manoeuvres and had lost much of the benefit of its interlocking air defence fire.

The US dive bombers targeted the carriers Kaga and Akagi. Kaga was hit by bombs that detonated ordnance and set fire to aviation fuel, as well as disabling the carrier’s bridge. Her crew fought the fires for a long time but eventually abandoned ship around 1700. In the meantime, unsecured ordnance on deck and bombs aboard planes waiting to take off, also detonated aboard Akagi. At 1040 her engines failed, and she burned until abandoned later in the day.

As Kaga and Akagi burned after the attack by USS Enterprise’s air group. Sōryū was targeted by dive bombers from USS Yorktown. Three bomb hits near her elevators detonated ordnance and started fires. Her crew were ordered to abandon ship at 1045, though Sōryū remained afloat until just after 1920 when – despite efforts to save her – she sank.

The confusion among the Japanese carrier force may have saved Hiryū from attack; she remained undamaged and launched a strike that followed USS Yorktown’s strike planes home. Their strike scored three hits on USS Yorktown and reduced her speed to 6 knots. This was partially remedied, with the carrier soon able to make 20 knots. However, a second strike inflicted crippling damage that eventually, at 1500, forced USS Yorktown’s crew to abandon ship.

Just minutes before the order was given to abandon USS Yorktown, Hiryū was attacked by rearmed planes from USS Enterprise. Some attacked nearby battleships, without much success, but four bombs hit Hiryū. Her situation seemed initially redeemable, with assistance from other vessels partially containing her fires. However, her own firefighting equipment had been disabled and once the fire spread below nothing more could be done to save her. She, too, was abandoned at around 0350 the following day.

Up to this point the Imperial Japanese Navy had lost four carriers for sure and the US Navy might potentially lose one, but it seemed that USS Yorktown might again survive serious damage. She was taken under tow and boarded by a salvage crew but presented an easy target for the Japanese submarine I-168 and was sunk by torpedo.

Meanwhile, after an abortive run to bombard Midway, the Japanese cruisers Mogami and Mikuma collided whilst evading a torpedo attack by a US submarine. They were attacked by aircraft as they withdrew; Mogami was badly damaged and Mikuma sunk.

Victory at Sea Rulebook

Within the Victory at Sea rulebook, you’ll find a scenario allowing you to refight the Battle of Midway on the tabletop, in which US dive-bombers attempt to sink as many Japanese carriers as possible. This is just one of many of such historical scenarios to be found in the book; the asymmetrical force composition in many of these scenarios makes such games feel very unique to play; there’s a great variety to be found within its pages. Full contents:

- The complete rules for fighting naval battles, including the use of aircraft, submersibles and coastal defences.

- Detailed background notes on the progression of naval warfare through WWII.

- 28 historic scenarios, covering every theatre over the span of the whole war.

- Exhaustive fleet lists for all the major belligerents, providing game statistics for hundreds of unique ships, submarines, aircraft and MTBs.

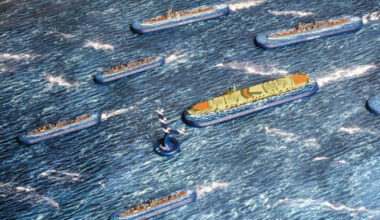

Carriers & Aircraft Flights

Since the Game’s launch, the ship roster has grown to incorporate a greater variety of carriers and aircraft flights, making carrier battles in Victory at Sea a more viable prospect – which will only embellish further as the range continues to expand.

1 comment

Can anyone lead to. How to put the towers on enterprise?

Comments are closed.