This is the first in a multi-part series on how travel around Antares works and, more importantly, how we can map it for own games and campaigns. First off, we need to run through an overview of how Antares works and some of the gritty detail that shapes the ways that we might map the giant Nexus that is Antares.

1.1 An Introduction To the Surface of Antares

The surface area of the Antares Nexus is huge. At a circumference of around 258 Astronomical Units (AU, 1×AU being the distance from earth to the Sun), it would fit all the major planets of our own star system and the orbit of Pluto within its volume. But even this amount of space is tight given the number of gates that are now on the surface of Antares: around 5.5 million.

Which means an identical number of connected systems, perhaps 5-10 times that number of connected planets and a connected population well into the trillions, if not tens of quadrillions. The numbers are mind-boggling. Of course, panhumans, in all their phenotypes, are in the majority in the 7th PanHuman Age, but there are still vast numbers of Vorl and Tsan Ra, and a fair number of other species such as Krasz, Askar, Ghar (don’t spit!), and others we have not yet created.

And outside the peaceful areas of the inner Concord and Senatex, and the controlled areas of the Prosperate, the citizens of many planets live in fear of a hostile takeover – the perils of space and gate travel notwithstanding.

From a gamer’s perspective, the great thing is that even when we take out the peaceful systems under Senatex, Concord or Vorl control, it gives us a lot of space to play with and in which we can position our games. We can even create our own version of the Antarean surface and locate our own campaigns somewhere on its surface.

All the systems connected to by Antares are significant in some respect. This may be due to being populated already, or they may have artefacts or ruins that may be of importance to Antarean civilisations, or have significant resources, some are simply connected because they are highly unusual in some respect, typically by having some physical or scientific oddity within or around them.

This significance just means we can be guaranteed of something juicy at the end of a gate. Before we go ahead with mapping, locating and creating systems, we need to understand other factors of important to interstellar travellers: How do travellers get around? How fast can they travel? How far apart are the gates of Antares? What systems are we talking about?

These series of articles are designed to help us to understand what Antarean travellers need and then create our own maps that reflect the nature of Antares.

And give us some fun at the same time!

Before we go further we need to know some terminology. Throughout these articles we use the term AU, or Astronomical Unit, as a translation of the Antarean SAU, or Standard Astronomical Unit. An Antarean SAU is based on what is known of the long-lost origin planet Old Earth and its orbit around its primary, Old Sol. A standard unit of measurement on Antares is the yan, which is about five metres, but we stick here with metres and kilometres for ease of reference and comparison. Antareans measure ship velocity in space in SOLs, where 1 SOL is 1/100 of the speed of light: 10 SOLs is 1/10 of the speed of light and 0.1 SOL is 1/1000 of light speed. Space battles typically take place at speeds of SOL 0.1 and slower.

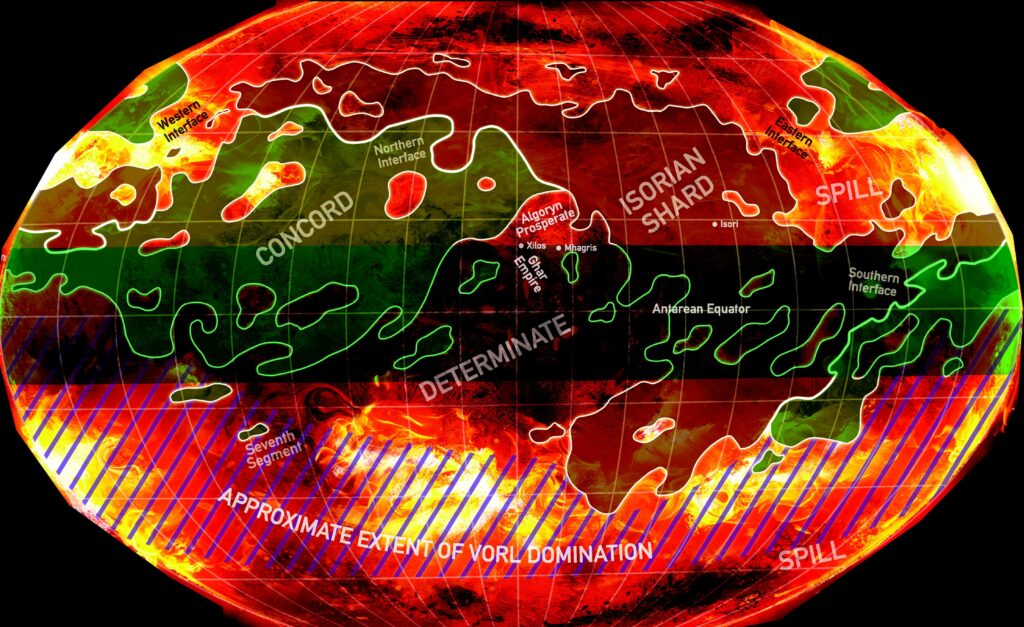

We also need to note the term ‘Spill’ as seen in several areas on the Antarean projection below. ‘Spill’ is used in several ways but when referring to areas on Antares surface it refers to those regions outside of the control of the major interstellar factions. The terms ‘Spill Kingdom’, ‘Spill Fiefdom’, ‘Spill Federation’ and similar all refer to small nations of multiple systems that are located in the Spill regions. The Determinate, a hotbed of activity and interstellar warfare, is the largest and most heavily populated Spill region and is where the Ghar Empire and Algoryn Prosperate are located. A similar, frequently used term is ‘Interface’, used to show a major border between the two IMTel nations of the Isorian Senatex and PanHuman Concord. There is constant conflict along the Interfaces as the IMTel shards cannot help but combat the other. The qualifiers, such as Northern Interface or Southern Interface, are all in terms of their position relative to Isor, the most influential system in the 7th Age of PanHumanity on Antares and, of course, the creator of the IMTel.

1.2. A Brief Overview of Antarean Travel

Before we begin on the details of Antarean mapping, we need to remind ourselves of how to get around on Antares. The star-machine that is Antares acts as a central point on the surface of which ‘gates’ are created. Each gate can transport objects of up to around 5-6 km across from the gate’s position on Antares through a trans-dimensional tunnel to a gate on the fringes of a star system: one Antarean gate connects to one system gate.

As the Gatebuilders no doubt intended, this bypasses all the problems and time lags of interstellar travel as at no time does a ship travel faster than light. All a traveller has to do is enter a system gate, pop out on the surface of Antares, travel to another gate on Antares, enter it and pop out in a completely different star system which may be thousands of light years away.

Most of the time interstellar travellers do this in a starship specially fortified for the journey.

The dangers are numerous: not only do ships have to travel across the surface of a star and resist extreme temperatures, they also have to cope with plasma flows on the Antarean surface and eddies and storms caused by the rapid movement of Obureg overhead – Obureg being a vital component of the Antarean Nexus. Further, only around 43% (2.4 million) of the gates connect to or near the surface of Antares, so many more are up to 2AU beneath the surface and require some further risk from increased pressure and more vigorous plasma flows; indeed Antareans refer to a ‘critical depth’ – around 1AU down – beyond which ships suffer damage and run the risk of not returning to the surface.

That’s not quite the basics finished: we have to look at time.

Antarean gates not only connect points in space but in time. A gate to (say) Isor may connect to a time period that is totally different to one that connects, say, to Taskarr. This means that the Isorian real-space empire may never expand to meet one of the systems connected to the Senatex by an Antarean gate: even if it contacted the same system, the Antarean gate may have been connected way in the system’s past (probably not its future due to causality reasons, but that’s a different article).

Further, when traversing a gate, there is a fixed period of time that the journey takes whilst within the tunnel. This could be minutes, hours, a day or months and some gates have a travel time so long that they are regarded as inaccessible. So a ship enters a system-side gate, spends a finite amount of time within the tunnel, and exits the Antarean-side gate on the Antarean surface.

This is where another factor comes in: it has been proven that travel on the Antarean surface is subject to a time-dilation effect that can vary from 3:1 to as much as around 11:1 (measurements vary) with a usable average of around 5.6:1. When coupled with Obureg’s policing of velocity and conflict – the dwarf companion destroys any ship that goes too fast or attacks another – this means that travel must be at a maximum of SOL0.1, or 1/1000 of the speed of light between gates on Antares’ surface (still fast!). A journey between two ‘adjacent’ gates that takes around 6 hours experienced time, takes around 36 hours in ‘real’ time.

It is also worth noting here that gates do not allow any ship or object to enter them if they are travelling faster than SOL0.1. If a ship attempts to travel faster than this on the surface of Antares it, and everything around it, is destroyed by Obureg’s passage overhead. The only way to get over the time lag when on long journeys is to rise further from the surface of Antares where the time dilation effects are less, but even then there is a limit as to how far a ship can rise from Antares before Obureg causes it to be destroyed. So, for all intents and purposes, travel on distances of up to around 10 gates distance is almost always carried out on the surface of Antares.

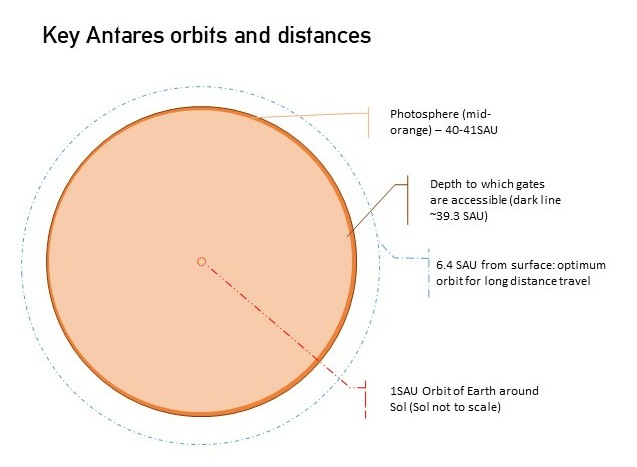

To complicate things still further, the density of gates on the Antarean surface varies depending on the latitude. So there are more gates at the equator than there are at higher latitudes. At the poles, gates are far apart whereas at the equator, they are relatively close to one another. The diagram ‘Key Antares orbits and distances’ shows some of these concepts and distances. The more keen-eyed players may note some subtle differences between this and that given in Splintering Shard:

These are purely down to our own understanding of Antares developing!

Despite the diagram and explanations, it’s all a bit messy, isn’t it? The next part in this series goes through the whole process of turning all this into something we can use for our own maps of Antares.

3 comments

The only part of BtGoA that I struggle with is the mental picture and understanding of how this works. I have been tempted to start work on a RPG to run BtGoA, alongside the wargame, but this facet has prevented me (this and a pandemic) thus far. Perhaps now I will once again consider this. I never quite got to grasp with the mechanics and physics of Antares once through a gate in order to find another. Did one leave a gate from ones system, appear on Antareas and then once the destination gate is found, does one enter down it or up it, or sometimes either? Can you see others exiting gates? Can one ship enter from one end while another enters from the other and pass unknowingly? Thank you so much, I can not wait to read the follow up articles to cure my ignorance. The support from this community, and from Warlord games in general, is one of my main reasons for playing Warlord Games games almost exclusively.

I just recently started reading the history of BtGoA in the rulebook yesterday, and this is exactly what I love about wargaming. Good mechanics make a game playable, but a good story makes it fun! And at least now I know what the heck these Gates are!

Comments are closed.