When Napoleon began his invasion of Russia in June 1812, he brought with him an army drawn from a score of conquered and allied nations, some 450,000 strong. When, less than six months later, his force straggled back into central Europe, nearly 380,000 were dead. Napoleon’s Grand Armee was a shattered wreck of its former self, and the Emperor’s air of invincibility had been proven false. While a grossly overstretched supply chain and the bitter Russian weather certainly accounted for most of the casualties, credit must be given to the doughty Russian troops who stood against Napoleon with grim determination, enduring often-horrific conditions to defy the Corsican’s ambitions.

The Russian army of the Napoleonic era was vast, with over 500,000 regulars and around 150,000 Cossacks and other irregular cavalrymen. Upon accession to the throne, Tsar Alexander I ordered General Michael Barclay de Tolly (a Russian through and through, despite his unusual mixed German and Scottish heritage and name!) to undertake a thorough modernisation of this immense force, recognising that it had become woefully outdated compared to other European militaries of the time. Barclay de Tolly rearranged the army using the French model, and attempted to standardise the equipment with the 1808 ‘Tula’ musket, although a bewildering variety of firearms of (usually low) quality remained in service throughout the Napoleonic Wars. Despite this handicap, the Russian infantryman proved a steadfast and determined opponent on the field.

The educated man serves in artillery

The dandy in the cavalry

The idler in the navy

The fool serves in the infantry

Russian Proverb

The average Russian infantryman at the time was likely to be a conscript, inducted into the army as part of a ‘levy of souls’ – literally a part of his village’s tax bill! Service was originally for ‘so long as one’s strength and health allow’ – in other words, life. In 1806, this was shortened to 25 years, but for all practical purposes this meant the same thing, and it was traditional for new recruits to be mourned by their village when leaving as though they were dead – the vast majority would never return home, even in peacetime. While they did receive pay, Russian private soldiers were in most respects just as firmly owned and controlled by the state as the vast numbers of serfs who were enslaved under the last bastion of European feudalism.

Discipline in the Russian army was often brutal, with a popular saying being “recruit three (men), beat two to death, train one”. While something of an exaggeration, it is certainly true that beatings were meted out with a frequency and severity surpassing other armies of the time – certainly no mean feat when the British Army’s infamous heavy-handedness is taken into account. This harsh treatment did, however, produce an infantryman of supreme fortitude, capable of enduring the worst hardships with a smile and marching seemingly for days on end. The staggering quantities of kvas beer and strong spirits they were issued no doubt helped, but the Russian soldier’s reputation for drunkenness is likely somewhat overblown, given the strict regime under which the army operated. Whatever the cause, they were incredibly resilient and capable of operating under the truly awful conditions encountered during Napoleon’s invasion.

Perhaps because of the poor quality of their muskets, the Russian infantry were famed for their use of the bayonet as a weapon of first resort. A Russian military manual of 1812 stated that “The bayonet is the true Russian weapon and the push of the bayonet is far more decisive than musketry”, and the legendary General Suvorov stated “The ball may lose its way, the bayonet never. The ball is a fool, the bayonet a hero.”. On several occasions, Russian commanders were unable to control their regiments, so eager were the troops to close with the enemy!

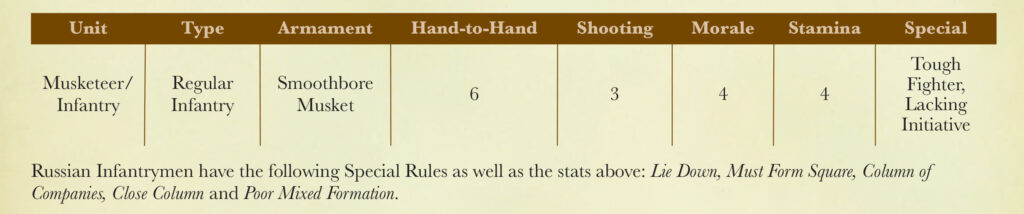

On the Black Powder tabletop, as detailed in A Clash of Eagles, Russian infantry receive a bonus to their Stamina, reflecting their uncanny ability to soak up enemy fire, but receive a -1 penalty to their shooting, demonstrative of their poor-quality muskets and weak marksmanship. They also have the Tough Fighters rule as befits their legendary prowess with the bayonet. The Lacking Initiative rule, however, prevents them from moving on Initiative, unless issuing a charge, representative of the often-poor quality of Russian officers and the rigid structure of the Russian army. As depicting an army in a transitional state, we have two plastic boxed sets of Russian infantry to bolster your forces, the first in the traditional Russian shako, suitable for 1809-1814, and the second in the kiwa shako, introduced in 1812.

Given the enormous size of the Russian army, we’ve also put together an Army Muster bundle deal for each period, each giving you a full Russian infantry brigade, with a free command with which to lead your new troops to victory. Drink up your kvas and stand to, soldier. The French are coming. For the Motherland, charge!