It is one of the most studied military conflicts in history, with over 237 named battles in addition to innumerable minor actions and skirmishes. Tactically, battles were still largely linear – regiments frequently fired all their ammunition only to be relieved by a second wave of troops passing through the line. However, the technology of war had become all the more destructive, and casualty rates were atrocious, leading to some historians citing the warfare of the American Civil War to be a precursor to that of the 1st World War over 50 years later.

Black Powder Epic Battles: American Civil War Players will soon be able to add a wealth of new tactical option to their forces, supplementing their infantry brigades with famous regiments and cavalry, adding a brand new dynamic to the game.

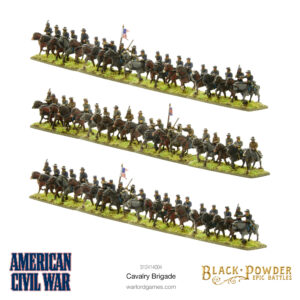

The Cavalry

The mounted arm of the Civil War armies evolved through a peculiar route during those four terrible years. In 1861, as regiments were raised and militias were mustered in, few cavalry regiments were raised. This was largely due to the expectation that the war would be short, coupled with the cost associated with a cavalry regiment compared to an infantry regiment, and also the much longer time required to train a soldier to ride and care for a horse compared to turning him into a competent infantryman. Therefore, although cavalry regiments were raised throughout the war, it was often the case that they formed an unusually small proportion of the total army when compared to their European cousins. So, whilst in Europe cavalry might still form a quarter to a third of the army, in America it might be as low as a tenth of an army’s total strength and rarely exceeded a fifth.

The early outings for the mounted arm proved promising – exploits such as Stuart’s charge with his 1st Virginia Cavalry at First Manassas demonstrated the dash and élan of some mounted units and set the media’s and public’s imagination ablaze with images of the glorious charge – particularly in the South.

Sadly, this was not to last. As the armies of both sides, and in all theatres, realised what the realities of the battlefield were, the place of the cavalry was relegated more to that of mounted reconnaissance, scouting and piquet duties. As with the infantry, the notion of closing with formed (and prepared) infantry or artillery in a headlong charge became almostunthinkable. The firepower of an infantry regiment was held to be sufficient to prevent the cavalry from charging home, and as with the infantry, the sensible trooper saw no benefit to be gained from such a risky venture.

And so was born the cavalry “raid”. This might be more than a simple dive into the enemy’s rear to burn a few supplies, though it could be that small. By the war’s closing stages it was not uncommon to see an entire cavalry division, even a corps, dispatched upon some errand of destruction.

As the uses of technology evolved over the course of the war – with improved weapons and firepower the cavalry finally came into their own as a battlefield arm – not in the form of a mounted breakthrough force, but as a force with high firepower able to hold ground or block an enemy. Ably supported by the horse artillery the cavalry might arrive ahead of the infantry and take vital ground. There was one enemy however, that the cavalry would still meet in a head on charge – other cavalry! The troopers of both sides carried pistols (perhaps more than one if Confederate) for the close or hand-to-hand combat and sabres were often, though not always carried.

So from having a limited battlefield role the cavalry evolved into a vital component of the army, particularly for the Union; perhaps still detached on its own mission but now able to trade blow for blow with the infantry through firepower and quite willing to deal with the enemy cavalry through pistol and sabre.

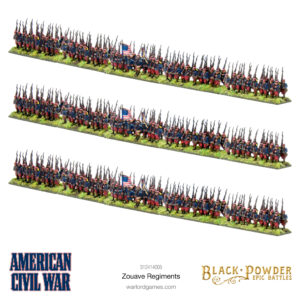

Zouave Regiments

In emulation of uniforms worn by some troops in French service several infantry regiments adopted zouave dress. The zouaves had historically stemmed from tribal units in French service in North Africa. Several of these regiments were taken into the French army and served during the Crimean War where one George B McClellan had been an observer. McClellan was duly impressed by their gallantry in action. Newspaper articles recounting their deeds spread their reputation and many American regiments, both North and South styled themselves as zouaves. American zouave regiments came into existence in three ways: either formed from zouave militia regiments, raised as zouaves from volunteers at the outset, or converted into zouaves during the war from existing regiments. In total over fifty such regiments were formed on both sides. Initially most were from the deep south where historical French settlement had been strongest, but by the war’s end most zouave regiments were to be found in Union armies.

What made the zouave regiments different was their uniforms. No more were there plain blue or grey coats with a weather-beaten slouch hat, but instead a selection of styles and colours that left many observers confused. To say that zouave uniforms could be gaudy, bordering on ridiculous perhaps, might be an understatement.

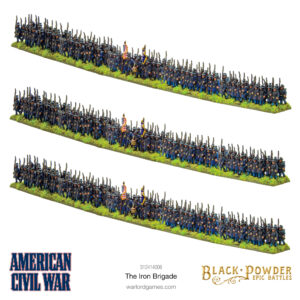

The Iron Brigade

The fledgling United States, having rejected all of the obvious benefits of a monarchical system of government, maintained an army that, by the very nature of the “republic”, could not contain any “guard” regiments, since there wasn’t really anyone worth guarding when compared to a monarch! Despite this enormous limitation on the esprit de corps of any army it was perhaps inevitable that some affection was transferred from the non-existent throne to the “senior” positions within the army. Since being first has always been considered best, the premier fighting formation of the Army of the Potomac became: 1st Brigade, 1st Division, I Corps.

In 1861 as the Northern armies were being formed, the 2nd Wisconsin Regiment arrived in Washington and was assigned to the 3rd Brigade, commanded by a regular officer – Colonel William Tecumseh Sherman. The other three regiments in the brigade were New Yorkers. The Wisconsin regiment gallantly attacked the Confederates at Bull Run, but – with so much of the Union army – was driven from the field. In the reorganization and expansions that followed the 2nd was moved into a brigade comprising the 6th Wisconsin and the 19th Indiana and was later joined by the 7th Wisconsin. The summer of 1862 saw the brigade near Washington DC. It did not join McClellan’s Peninsula campaign, but was involved in smaller actions until being heavily engaged at Second Bull Run under the command of Brig. Gen. John Gibbon.

Following that defeat the 24th Michigan joined the brigade making the fifth and final regiment of the brigade. Gibbon organised for the brigade to be re-uniformed and under his command they donned the uniform that became theirtrademark, blue frock coat and a tall black Hardee hat with a black ostrich plume. Hence their nickname: “The Black Hats”, whilst Gibbon referred to them as his “Iron Brigade”.

The brigade fought at Antietam in the Wheatfield against Jackson’s command and later at Fredericksburg, but it is for their performance at Gettysburg that they are best remembered. On July 1st 1863 The Iron Brigade moved into line to the west of Gettysburg. In the fields and woods there the brigade contributed massively to holding up the Confederate advance. In so doing the brigade virtually destroyed itself, nearly two-thirds of its number falling.