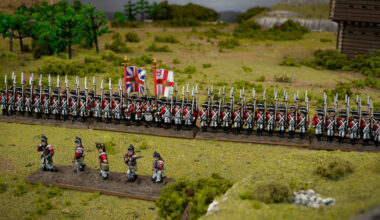

Black Powder Epic Battles: Revolution! is just around the corner. We’ve looked at all the many and varied troops making up the British and Continental forces – now it’s time to meet the commanders, who you can find in a handy box to add to your forces. We’ll begin with the British (and a German friend)!

Howe

We’ll begin with Sir William Howe. One of a trio of famous military brothers, Howe enlisted in the army at the age of 17, seeing action in the War of the Austrian Succession and the French & Indian Wars, where he would distinguish himself as the commander of General Wolfe’s light infantry during the capture of Quebec.

Howe would be ordered to America again when the revolution broke out, although as a Parliamentarian he had held sympathies for the colonists, and had opposed many of the punitive laws passed against them, but although he publicly proclaimed his unwillingness to serve militarily in America, privately he manoeuvred to be sent out as second-in-command to Thomas Gage in 1775.

In America, he would first see action under Gage at Bunker Hill, where he commanded the right flank to a victory – but one bought at a terrible cost in lives. When Gage was recalled to England, Howe assumed the mantle of Commander-in-Chief, North America. Initially, he was content to wait for reinforcements from England to begin his campaign, but would be compelled to evacuate Boston in the winter of 1776.

However, with newly arrived forces, Howe would launch his New York campaign, defeating the Continentals at Long Island in August. This victory earned him a Knighthood, but also brought significant criticism over his failure to press his advantage and capture more territory and prisoners. After a brief and unsuccessful attempt at a peace conference, Howe’s forces captured and held New York, driving George Washington’s troops across the Delaware. Sticking firmly to his plans, Howe once again refused to push his advantage. In hindsight, he may well have been able to defeat the Continental Army entirely had he been more aggressive.

In the 1777 campaign season, Howe’s objective was the Patriot capital of Philadelphia. After attempting and failing to draw Washington’s forces into a decisive battle in New Jersey, Howe’s forces embarked for their advance on Philadelphia. An amphibious landing was made in Maryland, and after a swift campaign of manoeuvre and small-scale engagements, Howe managed to occupy Philadelphia on 26th September. Although he was able to hold and consolidate his position, miscommunication and rivalry between Howe and General Burgoyne (who was commanding operations in the north) meant that he failed to pursue Washington or support Burgoyne’s troops in their Saratoga campaign, contributing to their eventual defeat. In October he resigned his role as commander in chief, citing a lack of support for his campaign, but this would not be accepted until April of 1778. Bizarrely, an enormous festival was held in his honour before he departed!

In Black Powder, we rate Howe as an excellent tactician with a Staff Rating of 9, but represent his unwillingness to follow up on his successes with the Timid special rule, making him less likely to issue orders to his men to advance on the foe! With good commanders assisting him, he’s more than capable of leading a force to victory – you’ll just need to make sure you can capitalise!

Cornwallis

Next up we’ve a man who served ably under Howe – Lieutenant-General Charles, 2nd Earl Cornwallis. We’ll call him Cornwallis for short!

A veteran of the Seven Years’ War in Europe, Cornwallis sailed for North America in 1776 as the Colonel of the 33rd Foot, first seeing action in the unsuccessful Battle of Sullivan’s Island. Following this, he joined Howe’s forces, acting as his second-in-command during the capture of New York, and beyond. In 1777 he was heavily occupied in defending against Washington’s forces in New Jersey, notably being defeated at the Assunpink Creek, before embarking to join Howe’s Philadelphia campaign.

Commanding the British light infantry in Howe’s march on Philadelphia, Cornwallis proved to be an able leader, helping to secure the wider area before the close of the campaigning season. Returning to England on leave, when he came back to America he found himself second in command of British forces in North America, following Howe’s resignation and replacement by Clinton. With the French entry into the war, British troops evacuated Philadelphia to concentrate on the defence of New York, and Cornwallis performed excellently at the Battle of Monmouth. However, his wife’s ill health prompted an urgent return to England in December 1778. Devastated by her death in February 1779, he returned to America, and would essentially be given a free reign to command British operations in the South.

With the capture of Charleston, Cornwallis operated under the mandate of securing British gains and pacifying North and South Carolina, before moving his operations into Virginia. Although he remained a capable commander, defeating the Continental Army at the Battle of Camden, Cornwallis’ forces were arguably too small to properly accomplish the task at hand, and over the following years skirmishes and sickness depleted his numbers. With the arrival of more French and Continental forces, Cornwallis linked up with newly arrived British troops in Virginia, but would eventually become trapped at Yorktown. The siege began on 28th September 1781, and ended on October 19th with Cornwallis’ surrender. This defeat was, in essence, what led to the end of the war, and the success of the American Revolution.

On the tabletop, Cornwallis’ skill as a tactician is well-represented by his Staff Rating of 9, and in addition the respect his men held him in allows him to make any unit he is in base contact with Elite 4+ – a great choice for any British commander looking to take the fight to the rebellious colonials!

Tarleton

The third of our British commanders is a man who’s currently serving as this month’s Soldier of Fortune figure, albeit in 28mm – Lieutenant-Colonel Banastre Tarleton!

The son of a wealthy Liverpool family, and a rather hard carouser in his youth, Tarleton joined the cavalry aged 21, and sailed to America as part of Cornwallis’ reinforcing troops. After helping capture the rebel general Charles Lee in 1776, Tarleton would be promoted to captain, and spent much of 1777 and 1778 commanding infantry rearguard detachments under General Clinton.

When British forces sailed south to capture Charleston in 1779, Tarleton – with a reputation for brave and effective service – was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel, and given command of the British Legion. This was an elite force of light cavalry and infantry designed for reconnaissance and other such independent operations. Under his command, the Legion would gain a reputation for ruthless efficiency, but also became feared and despised for their brutality, frequently being accused of massacring prisoners. Tarleton himself became a figure of fear, but was equally respected for his obvious abilities as a commander, distinguishing himself in the eyes of both the public and military during the southern campaigns.

At Cowpens in 1781, Tarleton’s overconfidence and impetuosity led to a stinging defeat at the hands of Daniel Morgan, but after this he continued to serve as the eyes and ears of Cornwallis’ forces, right up to the defeat at Yorktown. Although a hated figure in the eyes of American Patriots, Tarleton returned to England after the war as a feted hero, and was certainly one of the most skilled commanders of light cavalry forces of the entire conflict.

With a Staff Rating of 8, which rises to 9 if he’s issuing a charge of ‘Follow me!’ order, Tarleton’s a fantastic choice to lead your British light infantry and cavalry forces against the Americans. In addition, any unit he leads into melee gains the Tough Fighters rule, rewarding him for getting properly stuck in!

Riedesel

Our final British commander isn’t actually British at all! Friedrich, Baron von Riedesel, was a native of the German state of Hesse, and as the name suggests would be one of the senior commanders of the ‘Hessian’ allied troops who fought for the British cause.

Riedesel would join the military at 17, going to fight in the Seven Years’ War, where he would see action as a staff officer to the Duke of Brunswick, and later go on to command a pair of Brunswick regiments in battle. When, in 1776, agreements were signed with a number of German states to provide badly needed troops to the British effort in America, Riedesel would be promoted to Major-General, and placed in command of the Brunswick contingent. Arriving in Quebec in June of that year, his troops participated in the final defeat of the American invasion of Canada. In 1777, Riedesel would be placed in command of all of the Hessian and Native American (‘Indian’) forces under Burgoyne for the Saratoga campaign.

Here, Riedesel proved to be an excellent commander, particularly able to adapt to the harsh terrain, and a major proponent of light infantry tactics, at which his forces were some of the best. Despite frequent disagreements with the decisions of Burgoyne and other British commanders (who very seldom heeded Riedesel’s advice and hard-won experience as a professional soldier), he would remain loyally with the army all the way to its defeat at Saratoga in 1777. After Burgoyne’s surrender, Riedesel would be captured (along with his wife, who accompanied him on the campaign!), spending a year on parole before being exchanged for the rebel general Benjamin Lincoln. He would thereafter command a series of garrisons, before leaving America in 1783.

As befits one of the most capable professional officers in British service during the Revolution, we give Riedesel a special rule granting all infantry units in his brigade Superbly Drilled, making him a fantastic choice to lead your Hessians into battle. When paired with his Staff Rating of 8, you can rely on Riedesel to get the job done – provided you listen to his suggestions!